By now, if you read this blog, I assume you at least have a passing familiarity with massively online open courses (MOOCs), the “disruptive” technology set to flip higher education on its head (or not). Such courses typically involve tens of thousands of learners, and they are associated with companies like Coursera, Udacity, and EdX. To facilitate a 50,000:1 teacher-student ratio, they rely on an instructional model requiring minimal instructor involvement, potentially to the detriment of learners. As the primary product of these companies, MOOCs demand monetization – a fancy term for “who exactly will make money off of this thing?”. None of these companies have a plan for getting self-sufficient let alone profitable, and even non-profits need sufficient revenue to stay solvent.

Despite a couple of years of discussion, the question of monetization remains largely unresolved. MOOCs are about as popular as they were, they still drain resources from the companies hosting them, and they still don’t provide much to those hosts in return. The only real change in the year following “the year of the MOOC” is that these companies have now begun to strike deals with private organizations to funnel in high performing students. To me, this seems like a terrifically clever way to circumvent labor laws. Instead of paying new employees during an onboarding and training period, business can now require employees to take a “free course” before paying them a dime.

Given these issues, you might wonder why faculty would be willing to develop (note that I don’t use the word “teach”) a MOOC. I’ve identified two major motivations.

Some faculty motivate their involvement in MOOCs as a public service – in other words, how else are you going to reach tens of thousands of interested students? The certifications given by MOOCs are essentially worthless in the general job marketplace anyway (aside from those exploitative MOOC-industry partnerships described above). So why not reach out to an audience ready and eager to learn just because they are intrinsically motivated to develop their skills? This is what has motivated me to look into producing an I/O Psychology MOOC. But I am a bit uncomfortable with the idea of a for-profit company earning revenue via my students (probably, eventually, maybe), which is why I’ve been reluctant to push too fast in that direction. Non-profit MOOCs are probably a better option for faculty like me, but even that has unseen costs.

The other major reason faculty might develop a MOOC is to gain access to a creative source of research data. With 10000 students, you also have access to a research sample of 10000 people, which is much larger than typical samples in the social sciences (although likely to be biased and range restricted). But this is where I think MOOCs can become exploitative in a different way than we usually talk about. I concluded this from my participation as a student in a Coursera MOOC.

I’m not going to criticize this MOOC’s pedagogy, because frankly, that’s too easy. It suffers from all the same shortcomings of other MOOCs, the standard trade-offs made when scaling education to the thousands-of-students level, and there’s no reason to go into that here. What I’m instead concerned about is how the faculty in charge of the MOOC gathered research data. In this course, research data was collected as a direct consequence of completing assignments that appeared to have relatively little to do with actual course content. For example, in Week 4, the assignment was to complete this research study, which was not linked with any learning objectives in that week (at least in any way indicated to students). If you didn’t complete the research study, you earned a zero for the assignment. There was no apparent way around it.

In my experience on one of the human subjects review boards at my university, I can tell you emphatically that this would not be considered an ethical course design choice in a real college classroom. Research participation must be voluntary and non-mandatory. If an instructor does require research participation (common in Psychology to build a subject pool), there must always be an alternative non-data-collection-oriented assignment in order to obtain the same credit. Anyone that doesn’t want to be the subject of research must always have a way to do exactly that – skip research and still get course credit.

Skipping research is not possible in this MOOC. If you want the certificate at the end of the course, you must complete the research. The only exception is if you are under 18 years old, in which case you still must complete the research, but the researchers promise that they won’t use your data. We’ll ignore for now that the only way to indicate you are under 18 is to opt-in – i.e. it is assumed you’re over 18 until you say otherwise (which would also be an ethics breach, at least at our IRB).

Students never see a consent form informing them of their rights, and it seems to me that students in fact have no such rights according to the designers of this MOOC. The message is clear: give us research data, or you can’t pass the course.

One potential difference between a MOOC and a college classroom is that there are no “real” credentials on the line, no earned degree that must be sacrificed if you drop. The reasoning goes: if you don’t want to participate in research, stop taking the MOOC. But this ignores the psychological contract between MOOC designer and student. Once a student is invested in a course, they are less likely to leave it. They want to continue. They want to succeed. And leveraging their desire to learn in order to extract data from them unwillingly is not ethical.

The students see right through this apparent scam. I imagine some continue on and others do not. I will copy below a few anonymous quotes from the forums of students who apparently did persist. One student picked up on this theme quite early in a thread titled, “Am I here to learn or to serve as reseach [sic] fodder?”:

I wasn’t sure what to think about this thread or how to feel about the topic in general, but now that I completed the week 4 assignment I feel pretty confident saying that the purpose of this course is exclusively to collect research data… I don’t know that it’s a bad thing, but it means I feel a bit deceived as to the purpose of this course. Not that the research motives weren’t stated, but it seems to me that the course content, utility, and pedagogy is totally subordinate to the research agenda.

The next concerns the Week 6 assignment, which require students to add entries to an online research project database:

So this time I really have the impression I’m doing the researchers’ work for them. Indeed, why not using the thousands of people in this MOOC to fill a database for free, with absolutely no effort? What do we, students, learn from this? We have to find a game which helps learning, which is a good assignment, but then it would be sufficient to enter the name of the game in the forum and that’s it. I am very disappointed by the assignments for the lasts weeks. In weeks 1 and 2 we had to reflect and really think about games for learning. Then there was the ‘research fodder’ assignment. And this week we have to do the researchers’ job.

In response to such criticisms, one of the course instructors posted this in response:

Wow! Thanks for bringing this up! In short, these assignments are designed to be learning experiences. They mirror assignments that we make in the offline courses each semester. I’m really sorry if you, or anyone else felt any other way. It was meant to try and make the assignments relevant, and to create “course content on the fly” so that the results of the studies would be content themselves.

That strikes me as a strange statement. Apparently these assignments have been used in past in-person courses as important “learning experiences” but are also experimental and new. It is even stranger in light of the final week of the class, which asks students to build a worldwide database of learning games for zero compensation without any followup assignments (to be technical: adding to the database is mandatory whereas discussing the experience on the forums – the only part that might conceivably be related to learning – is optional). So I am not sure what to believe. Perhaps the instructors truly believe these assignments are legitimate pedagogy, but we’ll never really know.

As for me, although the lecture videos have been pretty good, I have hit my breaking point. In the first five weeks of the course, I completed the assignments. I saw what they were doing for research purposes before now but decided I didn’t care. Week 6 was too much – when asked to contribute data to a public archive, I decided that getting to experience this material was not worth the price. Perhaps I could watch the videos this week anyway, but I don’t feel right doing it, since this is the price demanded by the instructors. Even right at the finish line, I will not be completing this MOOC, and I can only wonder how many others dropped because they, too, felt exploited by their instructors.

![]() In an upcoming issue of Social Science Computer Review, Villar, Callegaro, and Yang1 conducted a meta-analysis on impact of the use of progress bars on survey completion. In doing so, they identified 32 randomized experiments from 10 sources where a control group (no progress bar) was compared to an experimental group (progress bar). Among the experiments, they identified three types of progress bars:

In an upcoming issue of Social Science Computer Review, Villar, Callegaro, and Yang1 conducted a meta-analysis on impact of the use of progress bars on survey completion. In doing so, they identified 32 randomized experiments from 10 sources where a control group (no progress bar) was compared to an experimental group (progress bar). Among the experiments, they identified three types of progress bars:

- Constant. The progress bar increased in a linear, predictable fashion (e.g. with each page of the survey, or based upon how many questions were remaining).

- Fast-to-slow. The progress bar increased a lot at the beginning of the survey, but slowly at the end, in comparison to the “constant” rate.

- Slow-to-fast. The progress bar increased slowly at the beginning of the survey, but quickly at the end, in comparison to the “constant” rate.

From their meta-analysis, the authors concluded that constant progress bars did not substantially affect completion rates, fast-to-slow reduced drop offs, and slow-to-fast increased drop offs.

However, a few aspects of this study don’t make sense to me, leading me to question this interpretation. For each study, the researchers report calculating the ratio of people leaving the survey early to people starting the survey as the “drop-off rate” (they note this as a formula, so it is very clear which should be divided by which). Yet the mean drop-off rates reported in the tables are always above 14. To be consistent with their own statements, this would mean that 14 people dropped for every 1 person that took the survey – which obviously doesn’t make any sense. My next thought was that perhaps the authors converted their percentages to whole numbers – e.g., 14 is really 14% – or flipped the ratio – e.g. 14 is really 1:14 instead of 14:1.

However, the minimum and maximum associated with the drop off rates in the Constant case are 0.60 and 78.26, respectively, which rules out the “typo” explanation. This min and max imply that for some studies, more people dropped than began the survey, but the opposite for other studies. So something is miscoded somewhere, and it appears to have been done inconsistently. It is unclear if this miscoding was done just in the tabular reporting or if it carried through to analyses.

A forest plot is provided to give a visual indication of the pattern of results; however, the type of miscoding described above would reverse some of the observed effects, so this does not seem reliable. Traditional moderator analysis (as we would normally see produced from meta-analysis) was not presented in a tabular format for some reason. Instead, various subgroup analyses were embedded in the text – expected versus actual duration, incentives, and survey duration. However, with the coding problem described earlier, these are impossible to interpret as well.

Overall, I was saddened by this meta-analysis, because it seems like the researchers have an interesting dataset to work with yet coding errors cause me to question all of their conclusions. Hopefully an addendum/correction will be released addressing these issues.

- Villar, A., Callegaro, M., & Yang, Y. (2014). Where am I? A meta-analysis of experiments on the effects of progress indicators for web surveys Social Science Computer Review, 1-19 DOI: 10.1177/0894439313497468 [↩]

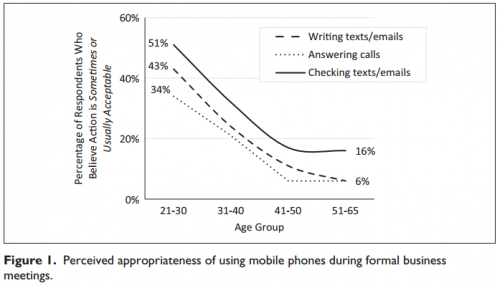

![]() In an upcoming article in Business Communication Quarterly, Washington, Okoro and Cardon1 investigated how appropriate people found various mobile-phone-related behaviors during formal business meetings. Highlights from the respondents included:

In an upcoming article in Business Communication Quarterly, Washington, Okoro and Cardon1 investigated how appropriate people found various mobile-phone-related behaviors during formal business meetings. Highlights from the respondents included:

- 51% of 20-somethings believe it appropriate to read texts during formal business meetings, whereas only 16% of workers 40+ believe the same thing

- 43% of 20-somethings believe it appropriate to write texts during formal business meetings, whereas only 6% of workers 40+ believe the same thing

- 34% of 20-somethings believe it appropriate to answer phone calls during formal business meetings, whereas only 6% of workers 40+ believe the same thing

- People with higher incomes are more judgmental about mobile phone use than people with lower incomes

- At least 54% of all respondents believe it is inappropriate to use mobile phones at all during formal meetings

- 86% believe it is inappropriate to answer phone calls during formal meetings

- 84% believe it is inappropriate to write texts or emails during formal meetings

- 75% believe it is inappropriate to read texts or emails during formal meetings

- At least 22% believe it is inappropriate to use mobile phones during any meetings

- 66% believe it is inappropriate to write texts or emails during any meetings

To collect these tidbits, they conducted two studies. In the first, they conducted an exploratory study asking 204 employees at an eastern US beverage distributor about what types of inappropriate cell phone usage they observed. From this, they identified 8 mobile phone actions deemed potentially objectionable: making or answering calls, writing and sending texts or emails, checking texts or emails, browsing the Internet, checking the time, checking received calls, bringing a phone, and interrupting a meeting to leave it and answer a call.

In the second study, the researchers administered a survey developed around those 8 mobile phone actions on a 4-point scale ranging from usually appropriate to never appropriate. It was stated that this was given to a “random sample…of full-time working professionals” but the precise source is not revealed. Rated appropriateness of behaviors varied by dimension, from 54.6% at the low end for leaving a meeting to answer a call, up to 87% for answering a call in the middle of the meeting. Which leaves me wondering about the 13% who apparently take phone calls in the middle of meetings!

Writing and reading texts and emails was deemed inappropriate by 84% and 74% of respondents respectively; however, there were striking differences on this dimension by age, as depicted below:

Although only 16% of people over age 40 viewed checking texts during formal meetings as acceptable, more than half (51%) of people over 20 saw it as acceptable. It is unclear, at this point, if this pattern is the result of the early exposure to texting by the younger workers or the increased experience with interpersonal interaction at work of the older population. Regardless, it will probably be a point of contention between younger and older workers for quite some time.

So if you’re a younger worker, consider leaving your phone alone in meetings to avoid annoying your coworkers. And if you’re an older worker annoyed at what you believe to be rude behavior, just remember, it’s not you – it’s them!

- Washington, M. C., Okoro, E. A., & Cardon, P. W. (2013). Perceptions of civility for mobile phone use in formal and informal meetings Business Communication Quarterly, 1-13 DOI: 10.1177/1080569913501862 [↩]