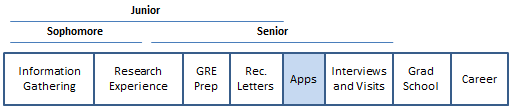

Grad School Series: Applying to Graduate School in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

Starting Sophomore Year: Should I get a Ph.D. or Master’s? | How to Get Research Experience

Starting Junior Year: Preparing for the GRE | Getting Recommendations

Starting Senior Year: Where to Apply | Traditional vs. Online Degrees | Personal Statements

Alternative Path: Managing a Career Change to I/O | Pursuing a PhD Post-Master’s

Interviews/Visits: Preparing for Interviews | Going to Interviews

In Graduate School: What to Expect First Year

Rankings/Listings: PhD Program Rankings | Online Programs Listing

So you want to go to graduate school in industrial/organizational (I/O) psychology? Lots of decisions, not much direction. I bet I can help!

While my undergraduate students are lucky to be at a school with I/O psychologists, many students interested in I/O psychology aren’t at schools with people they can talk to. I/O psychology is still fairly uncommon in the grand scheme of psychologists; there are around 7,000 members of SIOP, the dominant professional organization of I/O, compared to the 150,000 in the American Psychological Association. As a result, many schools simply don’t have faculty with expertise in this area, leading many promising graduate students to apply elsewhere. That’s great from the perspective of I/O psychologists – lots of jobs – but not so great for grad-students-to-be or the field as a whole.

As a faculty member at ODU with a small army of undergraduate research assistants, I often find myself answering the same questions over and over again about graduate school. So why not share this advice with everyone?

This week, I’d like to cover one of only two parts of a graduate school application that you have direct control over: your personal statement. This sometimes called a “statement of research interests” or “entrance essay” or similar. The core problem is always the same though: you need to write a page or two about yourself. So what do you write?

Before you get started, you need to plan. You shouldn’t just dive into a personal statement, because it says several things about you, and you want to make sure those messages are on target. Here’s what it says, and here’s what to do about it:

- This is the best quality of formal writing that you are currently capable of.

- The situation: Graduate school involves a lot of writing. A lot. You will be writing proposals, you’ll be writing term papers, you’ll be writing theses, you’ll be writing journal submissions, and on and on. Despite this, most graduate programs don’t explicitly teach you how to write – instead, they assume you learned it in college. As your potential mentors read your application, they’ll in part be thinking, “just how much work is it going to take for this person to become a decent science writer?”

- The solution: Treat your personal statement like a formal paper. Remember everything you’ve learned previously about how to write. You should have an introductory paragraph, several paragraphs of specific content (each with an appropriate topic sentence that explains the purpose of the remainder of that paragraph) and a conclusionary paragraph. You should ensure there are absolutely no spelling or grammatical errors. You should ask someone that doesn’t know you very well – and preferably someone who is a good writer – to read it over and tell you what they think. Often, your college or university will have a career services unit that will help you with this if your academic advisor won’t (or can’t) help.

- This explains why you are applying to graduate school (in I/O psychology).

- The situation: A lot of people apply to graduate school for terrible reasons. The most common terrible reason is, “I finished college and didn’t know what else to do.” This is pretty obvious in an unfocused personal statement, because it’s hard for you to explain exactly why you are going to graduate school. You need a good reason, and you need to explain it well. The reason this is important is because people without good reasons burn out. Grad school is hard. I like to refer to it as “trial by fire.” If you don’t come in with long term goals that you are fully committed to, you aren’t likely to finish – and that means advisors aren’t going to want to spend their time training you only for you to leave after a year.

- The solution: You really need to sit down and think about why you’re going to graduate school. This is different for every person, so there’s no single right answer here. Maybe you’ve always dreamed of being a professor. Maybe you’ve worked in human resources before and want to make it better. Maybe you just want to make a difference in the lives of employees and see applied I/O work as the best way to do that. All of these are fine answers – but your personal statement needs to explain your answer and how you came to it.

- This explains why you are applying to this particular graduate program.

- The situation: It’s fine if you want to apply broadly – in fact, I recommend it. But that doesn’t mean you can get away without doing in-depth research on each school you are applying to. Faculty want to know why you applied to their program. A single, untargeted, generic personal statement sent to a dozen different programs is one of the worst things you can do with your personal statement.

- The solution: Remember that applying to graduate school is very unlike applying to college: you’re not applying to take classes, you’re applying to work with a particular faculty member (or perhaps a few faculty members). If you have particular, targeted research interests, you need to say what they are, which faculty members you want to work with, and why. If you don’t have particular, targeted research interests, that’s fine too, so you should say that – but you still need to explain why you applied to this particular program. Did you talk to graduate students already in the program? Were you recommended to apply by your advisor due to the quality of the program? Something else? No matter what, you should have a different personal statement for every school you apply to. Don’t ever say you’re targeting a school because it is convenient to you (e.g. near family, lets you keep your job, etc.). If something like that is your only reason, you shouldn’t apply there.

- This explains how you’ve prepared for graduate school.

- The situation: Something you’re likely hear a lot in I/O graduate school is “The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior.” One thing that faculty want to know is how – specifically – you have prepared yourself for graduate school. This also speaks a bit to #2 above.

- The solution: If you’ve been following my blog’s advice since your sophomore year or earlier, you should have a lot of information to talk about here. You need to discuss what you learned in each research lab you’ve worked in and how this experience prepared you for graduate school. If you worked on particular projects that inspired you in your research interests, describe a specific anecdote or two (e.g. a particular research challenge you faced) and how you solved it and learned from it.

There are a few common problems with personal statements:

- Your statement is not your life story. While your 8th-grade teacher may have had an amazing influence over you that eventually led you to I/O psychology, it’s not very relevant to your application. Traumatic experiences (e.g. the death of a family member) are the same way. Although your great-grandfather’s death may have inspired you to do something with your life, it doesn’t really have much to do with your I/O career path. For each paragraph (and thus every sentence), you should ask: does it help the person reading this statement accomplish one of the four objectives listed above? If not, get rid of it.

- Your statement is not an opportunity to get creative. Remember point #1 above. This is a formal paper. It is the closest thing to scientific writing of yours that the selection committee is likely to see. Creative narratives, clever use of spacing, etc. make you memorable, but not in a way you want to be memorable. You want to be memorable for your qualifications. Don’t start your statement with a quote or cliche; for example, I cringe every time I see, “Life is a marathon” at the start of someone’s statement.

- Your statement should be about what you think and what you know, not what you did. When you apply to graduate school, you’ll also turn in a curriculum vitae (the academic equivalent of a resume). This should say which labs you worked for and when. It should also cover which classes you took. Don’t waste space in a personal statement reiterating this information; assume that the people reading your application have already seen your vita and build from there.

- Your statement is not exhaustive. Even if you have a ton of information that you want to share, and even if the program doesn’t provide a specific page limit, you should keep your personal statement under 2 pages. Maybe 3 if what you’re including is exceptionally compelling. Writing your personal statement should be an exercise in brevity – sharing as much critical information as possible in as small a space as you are able.

There’s no single “right way” to write a personal statement, but these guidelines will give you a good start to make a compelling argument for your acceptance.

SUBMISSION DUE DATE: June 2nd, 2014

SPECIAL ISSUE ON CFP: Assessing Human Capabilities in Video Games and Simulations

International Journal of Gaming and Computer Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS)

Guest Editor: Richard N. Landers

INTRODUCTION:

In video games and computer mediated simulations (GCMS), instructional designers and human resources professionals can develop virtual situations and environments that enable people to exhibit a wide range of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs; “O” includes a diverse set of constructs such as personality, preferences, interests). Often, direct measurement of these KSAOs outside of a computer-mediated environment is difficult, confounded, or costly. For example, in the instructional context, children may be more enthusiastic to demonstrate their mathematical fluency in a video game than on a paper-and-pencil test. When training firefighters, performance in a computer simulation may be used to assess job proficiency without the expense or risk of a live simulation.

In this issue, we plan to collect rigorous theoretical and empirical explorations of KSAO measurement using GCMS. Quantitative approaches, especially those containing concurrent or predictive validation data, are the highest priority, although any rigorous examination of KSAO measurement in GCMS will be considered.

OBJECTIVE OF THE SPECIAL ISSUE:

The purpose of this special issue is to explore and rigorously test methods for the measurement of human capabilities from GCMS.

RECOMMENDED TOPICS:

Topics to be discussed in this special issue include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Construct validation studies of KSAOs as measured in GCMS, especially those containing evidence of convergent/discriminant validity and/or

- criterion-related validity

- Development of theoretical models of GCMS-based assessment and empirical tests of those models

- Identification of KSAOs more readily measurable in GCMS than by using traditional approaches

- Application of psychometric theory (e.g. reliability, validity) to GCMS-based assessment, especially in relation to the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing and other professional guidelines

- Considerations of the appropriateness of classical test theory versus item response theory in GCMS-based assessment

- Explorations of faking and/or cheating in GCMS-based assessment and effects on validity

- Rigorous explorations of tentative or creative approaches to measuring KSAOs in GCMS

- Current best practices for practitioners seeking to conduct assessment using GCMS based upon the empirical literature

- Current best practices for scholars related to construct specification, research design, and statistical approaches to studying assessment in GCMS

SUBMISSION PROCEDURE:

Researchers and practitioners are invited to submit papers for this special theme issue on Assessing Human Capabilities in Video Games and Simulations on or before June 2nd, 2014. Authors are encouraged to contact RNLANDERS@ODU.EDU well ahead of the submission deadline to discuss the appropriateness of their submissions. All submissions must be original and may not be under review by another publication. INTERESTED AUTHORS SHOULD CONSULT THE JOURNAL’S GUIDELINES FOR MANUSCRIPT SUBMISSIONS at http://www.igi-global.com/journals/guidelines-for-submission.aspx. All submitted papers will be double-blind peer reviewed. Papers must follow APA style for reference citations.

ABOUT:

International Journal of Gaming and Computer Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS)

IJGCMS is a peer-reviewed, international journal devoted to the theoretical and empirical understanding of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations. IJGCMS publishes research articles, theoretical critiques, and book reviews related to the development and evaluation of games and computer-mediated simulations. One main goal of this peer-reviewed, international journal is to promote a deep conceptual and empirical understanding of the roles of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations across multiple disciplines. A second goal is to help build a significant bridge between research and practice on electronic gaming and simulations, supporting the work of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. This journal is an official publication of the Information Resources Management Association

www.igi-global.com/IJGCMS

Editor-in-Chief: Richard Ferdig

Published: Quarterly (both in Print and Electronic form)

PUBLISHER:

The International Journal of Gaming and Computer Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS) is published by IGI Global (formerly Idea Group Inc.),

publisher of the “Information Science Reference” (formerly Idea Group Reference), “Medical Information Science Reference”, “Business Science Reference”,

and “Engineering Science Reference” imprints. For additional information regarding the publisher, please visit www.igi-global.com.

All inquiries should be should be directed to the attention of:

Richard N. Landers

Associate Editor

International Journal of Games and Computer Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS)

E-mail: RNLANDERS@ODU.EDU

All manuscript submissions to the special issue should be sent through the online submission system:

http://www.igi-global.com/authorseditors/titlesubmission/newproject.aspx

![]() In an upcoming issue of Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, Grohol, Slimowicz and Granda1 examined the accuracy and trustworthiness of mental health information found on the Internet. This is critical because 8 of every 10 Internet users has searched for health information online, including 59% of the US population. They concluded that information found in early Google and Bing search results is generally accurate but low in readability. The following websites were identified as popular, generally reliable sources of mental health information: Help Guide.org, Mayo Clinic, National Institute of Mental Health, Psych Central, Wikipedia, eMedicineHealth, MedicineNet, and WebMD.

In an upcoming issue of Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, Grohol, Slimowicz and Granda1 examined the accuracy and trustworthiness of mental health information found on the Internet. This is critical because 8 of every 10 Internet users has searched for health information online, including 59% of the US population. They concluded that information found in early Google and Bing search results is generally accurate but low in readability. The following websites were identified as popular, generally reliable sources of mental health information: Help Guide.org, Mayo Clinic, National Institute of Mental Health, Psych Central, Wikipedia, eMedicineHealth, MedicineNet, and WebMD.

Because 77% of Internet users only look at the first page of search results, these authors examined websites found on the first two pages of search results (20 websites) on Google and Bing for each of 11 major mental health conditions (e.g. anxiety, ADHD, depression), resulting in 440 total rated websites. This struck me as peculiar though, since there should be substantial overlap between Google and Bing – so most likely, some cases were represented multiple times.

After the sites were collected, two graduate student coders (the last two authors, presumably) made ratings on all 440 websites for quality of information presented, readability, commercial status, and the use of the HONCode badge. HONCode is a sort of seal of approval for health websites from an independent regulatory body.

The found, among other things:

- HONCode websites generally contained higher quality information than websites without HONCode certification.

- Commercial websites generally contained lower quality information than non-commercial websites.

- HONCode websites were generally harder to read (higher grade level) than websites without HONCode certification.

- Commercial websites were generally harder to read than non-commercial websites.

- 67.5% of websites were judged to be of good or better quality based upon a generally agreed-upon standard (above a 40 on the DISCERN scale).

Statistically, this study had two peculiar features. First, there is the likely non-independence problem described above (websites were probably in their dataset multiple times). Second, most of their analyses were done via simple correlations, which have a very simple calculation for degrees of freedom: n – 2. Thus, degrees of freedom for all of the correlations they calculated (with the exception of the “Aims Achieved”, which had a lower n for a technical reason), ignoring the independence problem, should be 438. The degrees of freedom for Aims Achieved should be 396. However, in the article, these degrees of freedom are either 338 or 395. So something odd is going on here that is not explained. Perhaps duplicates have been eliminated in these analyses, but this is not stated.

One additional caveat: the owner of Psych Central (identified as one of the reliable sources of mental health information) was the first author of this study. I doubt he would fake information just to get his website mentioned in a journal article, so this probably isn’t much of a concern.

Overall, I am pleased to see that the most common resources available to Internet users on mental health are generally of reasonable quality, and I feel fairly confident in this finding. Like the authors, I am concerned that readability of the most popular websites is generally low. The mean grade level was 12, indicating that a high school education is required to understand the typical popular health website. That seems a bit high, especially considering younger people are most likely to turn to the web first as a source of information about their mental health. Hopefully this article will serve as a call to website operators to broaden their audience.

- Grohol, J. M., Slimowicz, J., & Granda, R. (2013). The quality of mental health information

commonly searched for on the Internet Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0258 [↩]