![]() In a recent issue of Human Resource Management Journal, Godard1 provides a provocatively-titled opinion piece: “The psychologisation of employment relations?” The central arguments of this paper are that 1) human resources management (HRM) is interdisciplinary, 2) industrial relations has historically been an important part of HRM, 3) organizational behavior has taken over HRM, pushing out industrial relations, 4) I/O psychology has taken over organizational behavior, pushing out traditional organizational behaviorists, and 5) these events have conspired to reduce the overall value of HRM. Clearly, such a paper requires a response, which was likely its intention. There is no way for me to respond to Godard’s entire argument in a blog post, but I thought I’d hit some highlights.

In a recent issue of Human Resource Management Journal, Godard1 provides a provocatively-titled opinion piece: “The psychologisation of employment relations?” The central arguments of this paper are that 1) human resources management (HRM) is interdisciplinary, 2) industrial relations has historically been an important part of HRM, 3) organizational behavior has taken over HRM, pushing out industrial relations, 4) I/O psychology has taken over organizational behavior, pushing out traditional organizational behaviorists, and 5) these events have conspired to reduce the overall value of HRM. Clearly, such a paper requires a response, which was likely its intention. There is no way for me to respond to Godard’s entire argument in a blog post, but I thought I’d hit some highlights.

Before going into Godard’s specific arguments, I think it’s important to note recent related goings-on within psychology to provide some context. Psychology is in general undergoing somewhat of a crisis, as the replicability and thus overall value of our research literature has being seriously questioned from within. Belief among US citizens that psychology even qualifies as a science is rather low. Within I/O psychology, the scientist-practitioner gap has been widening, driven partly by published research in mainstream journals (e.g. Journal of Applied Psychology, Personnel Psychology) becoming increasingly esoteric and impractical to apply in the real world, and driven partly by organizational belt-tightening, increasing the pressure on practitioners to use their time in a more billable fashion. These days, policies providing compensation to practitioners for publishing research are becoming increasingly uncommon, reducing the already-low publication rate by I/O practitioners. So things are not all well in I/O psychology, and I don’t think one can seriously claim otherwise.

Even given all that, Godard’s view is not reasonable to me for reasons I will explain momentarily. Here is Godard’s central concern:

What makes this potential takeover of particular concern is that it has been occurring at the same time that the study of labour relations (and trade unions) has continued to be narrowed and marginalised. Again, this has been especially so in business schools, where it has now increasingly come to be viewed as, at best, a subarea of HRM. Also important, and less noticed, has been the long-since-completed takeover of OB by I-O psychologists, and the corresponding displacement of the more sociological and ethnographic orientation associated with its main progenitor, the human relations school (Whyte, 1987). The result may be the gradual psychologisation of the study of not just HRM, but of employment relations in general (e.g. Sparrow and Cooper, 2003).

Let’s assume for now that this “takeover” has, in fact, occurred. Why does it matter? Again, I will let Godard tell you:

For example, a 2003 text by Paul Sparrow and Cary Cooper, entitled The Employment Relationship: Key Challenges for HR, has only 1.5 pages on employment law, nothing (that I could find) on labour law, trade unions or collective bargaining, and nothing on conflict other than the ‘intense emotional experience’ associated with a ‘breach’ in the ‘psychological contract’, and a brief (50-60 words) discussion of its

implications for exit, voice and loyalty (pp. 43-45). This text also contains only about a dozen lines on ‘employee involvement’ systems, all of which are in the context of their implications for commitment compared with those of job design. Although this book may be the exception rather than the rule, it is at minimum illustrative of the potential consequences of psychologisation should it continue.

So here lies the heart of the problem. With such an abundance of I/O psychology research driving OBHRM, more traditional (i.e. older) areas of HRM are being crowded out. The reason that this has occurred, Godard argues, is because 1) IO psychology’s attempts to simplify what are at their heart very complex problems more readily produces “answers” for management, which make it more attractive to both business school deans and managers-in-training, and 2) IO psychology has all the trappings of science but, in reality, is not a science. Instead, it is a sham. Another quote of interest:

Their research has six important components, all of which are largely consistent with this paradigm and ultimately with instrumental narcissism: (a) multiple authorships, with an extensive division of labour; (b) small-scale research questions; (c) extensive reliance on experimental research or survey methods, typically using students; (d) fixation on data analysis techniques, creating the appearance of scientifc sophistication; (e) extensive citation of other work; and (f) an absence of reflexivity…The consequence is that I-O psychologists do ‘better’ than their more traditional labour relations and HRM counterparts, who have traditionally done ‘messier’ institutional research that takes longer to come to fruition, and who are not as obsessed with citation rates. This is the case not just once they are hired, but also while they are in their graduate programmes, which seem to be designed mainly to generate publications rather than to ground students in substantive knowledge.

Ouch. Sort of fair – in that these have been and continue to be problems in parts of the I/O literature – but it is definitely overstatement, especially in regards to graduate training. The core of this statement is that “I/O psychologists oversimplify complex problems, using statistics that aren’t warranted to make their research appear meaningful when, in fact, it is not. They then pass this fake knowledge on to future students, who perpetuate meaningless research.” It is amusing to me that Godard would criticize oversimplification with such an oversimplification.

This type of oversimplification is common in Godard’s arguments, attributing to all of I/O psychology what is in reality much more complex. For example:

For example, selection and training courses increasingly focus on ‘soft skills’ having to do with attitudes and interpersonal qualities rather than technical and intellectual capabilities having to do with the actual ability to get things done. The result is a world in which employees are pleasant, but few have much of a clue as to what they are doing.

I cannot imagine a well-trained I/O psychologist advocating dropping technical skill requirements from the selection process. That is, to me, literally unbelievable. If technical requirements are dropped from selection procedures that already contain such requirements, I doubt it is the I/O psychologist making that recommendation. In the I/O psychology model, selection devices follow from job analysis, and well-done job analyses will contain technical requirements. End of story. I am not sure what type of I/O Godard has been observing to draw such conclusions.

I am left concluding from all of this that Godard is upset that industrial relations have been ignored in the growth of HRM to include I/O. Here is where we return to his idea that I/O has “taken over” HRM. In my read, despite Godard’s claim that HRM is “multidisciplinary”, this article is predicated on the assumption that there is only room for one perspective in HRM. That I/O has ruined that perspective and should be stopped.

This approach is bizarre to me. If business school deans are the problem, lobby to deans why industrial relations are important. If the research literature is the problem, build a literature more inclusive of the topics you find critical. If perspectives are missing in the I/O literature, add to that literature, altering and testing theory to include the components that are missing. That is the how the scientific method works. It is not an illusion we employ to make our work seem more credible. It is instead a flexible and powerful framework for testing ideas. It does not discriminate. If your industrial relations variables are really so important, add them to the models in the literature and see if you attain the dramatically greater prediction that you claim to be able to attain.

For all of Godard’s criticisms of I/O as explaining tiny amounts of variance that don’t ultimately matter to organizations, nowhere in this paper is the suggestion that our models be expanded to include such variables. Instead, psychology should be dropped entirely from HRM. That is, to me, is “throwing out the baby with the bathwater”.

Certainly I/O is overwhelmingly popular in HRM, but perhaps that is because I/O actually does bring value? Perhaps, despite its many failings (and I am first to agree that there are many!), it still manages to help organizations, managers, and employees to better meet their goals? Perhaps it is popular, and perhaps it is crowding out industrial relations, because the academic study of industrial relations has failed to demonstrate its own value to organizations? I imagine this is not a viewpoint that Godard considered.

More precisely though: Why is the solution to the “psychologisation of employment relations” to criticize psychology rather than to improve employment relations?

There are a couple of examples of this one-sidedness. The first is in Godard’s criticisms of an Academy of Management Annals paper entitled, “Employee voice behavior: integration and directions for future research”. Godard states:

Figure 2, reproduced from this paper, illustrates the problem. First, one is struck by the number of variables identifed, the arrows and boxes connecting them, and the lack of any effort to arrive at any deeper explanation for voice. Second, there is no identification of trade unions as a source of voice; indeed, the concept of voice in the figure appears to be entirely an individualistic one. The author does at one point acknowledge that there is an extensive literature in the field of labour relations and in HRM, but actually dismisses it on the grounds that authors in these fields ‘have not considered discretionary voice behavior, nor the causes and consequences of this behavior’ (p. 381). Third, the sole motive identified for voice is ‘to help the organization or work unit’. In this regard, the ‘integrated conceptualization’ that the author claims to have developed ‘from the various definitions in the literature’ deines voice as ‘discretionary communication… with the intent to improve organizational or unit functioning’ (p. 375). Apparently, neither interest conflicts nor injustice matter. This is only one illustration, but for anyone with an IR background it has to be an astonishing one, especially given that the topic is one that has long been central to IR as a field yet is now being psychologised (for more extensive critiques, see Barry and Wilkinson, 2013; Donaghey et al., 2013).

So where is the criticism of prior models from industrial relations lacking discretionary voice? Why not write a paper on “the industrialisation of HRM” criticizing how models in industrial relations never contain sufficient exploration of psychological variables? Let’s not forget that the purpose of theory is not to exhaustively describe a particular phenomenon, or else all theories would contain thousands of variables. As that classic quote by Box goes: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” The simple fact that variables are omitted from a theory does not, by itself, condemn that theory. To believe otherwise is to majorly misunderstand the purpose of theory.

The second major example of this one-sidedness:

The argument in this article may be accused of con?ating theory with practice. There are undoubtedly many with I-O psychology backgrounds who are less interested in manipulating workers to managerial ends than in helping create the conditions for a higher quality of work experience and a productive working life. There are also many who do not fully adhere to the scientised research paradigm that seems to have become predominant, and even among those who do, many who may have misgivings about this paradigm – even if they are not sure why.

One can just feel the condescension dripping from that paragraph. “They’re all wrong; perhaps an enlightened few feel how wrong they are but just aren’t smart enough to realize why!” My counter question: Why are the methods of industrial relations so infallible? I suspect only because they are so familiar.

If I/O psychology ignores industrial relations, industrial relations appears just as guilty of ignoring I/O psychology. Neither perspective is helpful. Perhaps organizations (and their employees!) would be better served if these fields learn from each other instead of providing blanket condemnations of a frightening “other”?

- Godard, J. (2014). The psychologisation of employment relations? Human Resource Management Journal, 24 (1), 1-18 DOI: 10.1111/1748-8583.12030 [↩]

Each month, the Society for Industrial & Organizational Psychology releases a newsletter describing current events in I/O Psychology. In the February issue, I noticed a brief article on an intriguing little study conducted by the SIOP Media Subcommittee, part of the SIOP Visibility Committee. Via the SIOP newsletter, the SIOP website, and social media, the committee asked I/O psychologists what they considered to be the top workplace trends for 2014. Since most of the trends they identified are within my research area, I thought I’d explore my take on this what these items mean and how much progress I/O psychology has made so far in exploring them. Here’s the list of trends, in order from hot to sizzling.

- Alternatives to Full Time Work. Temporary, part time, and contractor work is becoming an increasingly common model for modern businesses. As employees shift to part-time work, do their motivations for performing “good work” change? I/O certainly has models of job performance and its predictors, but most of the empirical work on these constructs was developed and tested on permanent positions. To what extent do these findings hold with temporary workers? Of all areas of I/O, I expect discussion of culture and climate to turn to this problem first.

- Telework. As technology improves, it is becoming more obvious that completing the technical requirements of many jobs does not require workers to be physically present in the office. So why not let them work from home, saving money on office space and other resources? The research literature on virtual teams has grown quite a bit in the last few years, but our understanding of completely remote workers is still quite limited. Much to be done here!

- Social Media for Employment-related Decisions. Social media is one of my personal areas of interest, in terms of both organizational learning and employee selection (evidenced by my lab’s work on social media in selection at SIOP this year). On both fronts, we know very little so far. It seems like we can get some degree of job-relevant information from social media, but it remains unclear what the best way to go about this is, or what the legality of that information ultimately is. Should we trust hiring managers to ignore information about protected class membership (sex, race, national origin, skin color, religion, disability, and others) when scanning social media for information about job applicants? Even if we trust hiring managers to ignore this information, would the courts believe us? I suspect not.

- Work-Life Balance. Of the list of top trends, this is probably the most well-explored on the list within I/O. Work-family conflict (and family-work conflict) are both linked with a variety of negative outcomes for workers. But as technology becomes omnipresent in people’s lives, the line between work and home continues to blur. For many (like myself!), there essentially is no line. With Twitter, our private lives and public lives are often the same. What effect does this have on well-being and job performance? Will people burn out faster than ever before?

- Integration of Technology into the Workplace. Another of my research areas. Employees are now able to reach out via social media to others in their organizations when they need help – via email, via instant messaging, via teleconference – but are more tempted than ever by the siren song of easy, quick social interaction. How can social media be leveraged within organizations to bring the potential benefits without the drawbacks? We don’t know yet – and that’s what I aim to learn. Technology is increasingly being used to monitor employees in ways not even conceivable 10 years ago – including tracking specific employee movements throughout the workday. What impact does all this dehumanization have upon productivity and retention?

- Gamification. Another research area! Gamification has taken the business world by storm, with gamification “gurus” and “experts” rising up all over the place. The dirty truth, of course, is that no one yet really know what makes it work. Nearly zero empirical research is available to explore these effects, although there are three at SIOP 2014 (two of which are from my lab). The big problem is that many gamification efforts do fail – and fail badly – with a wide variety of unintended negative consequences. Does gamification need to crash before people use it selectively and carefully, when there is a clear reason to do so? I hope the crash can be avoided, but it looks like we’re headed that direction.

- New Ways to Test. Yet another research area, with more SIOP presentations! Many people want to complete assessments on whatever device they have handy. That means tablets and mobile phones. The problem with BYOD (bring-your-own-device) is that your assessment needs to be reliable and valid on all of them – and this is notoriously difficult to test because of the sheer variety of such devices. Even desktop and laptop computers vary a bit in how they present the web – but this variation is nothing compared to the incredible range of mobile device interfaces (from 2″ to 7″ screens!). Fortunately, early research indicates that mobile and traditional devices don’t differ much in terms of reliability and validity. But more work is needed.

- The Talent Question. Now that organizations compete for talent on the Internet (and thus on a global level), how do you identify and attract the best of the best? If Google and Apple can snap up all the best IT talent from every school in the world, where does that leave everyone else? And as specialized skills that require deep levels of training become more common needs for organizations, how can organizations find these people at all? Unfortunately, online recruiting is probably the oldest yet understudied area on this list.

- Increasing Efficiency. The traditional I/O approach to helping organizations run lean has been to improve selection systems (you don’t need as many people if they are better people), improving training (if people know their jobs well, you don’t need as many backups) and to solve any specific personnel problems (troublemakers harming group performance, etc.). But post-recession, many organizations are already running lean – and need to do even more. At what point is there nowhere left to go? When is the only solution remaining to hire more personnel?

- Big Data. #1 on the list is Big Data. This is a bit of a hard concept for I/O’s I’ve talked to to deal with, because many believe we already “do” Big Data. “But I collected a 500-person validation study! That’s the sort of skill Big Data requires!” they say. It isn’t. I’ve only worked on one Big Data project myself – a 13.5 million case dataset. SPSS would not even open it, and that’s not even all that “big” in terms of Big Data, which starts at the point where traditional data analysis programs can’t handle the analyses you want to run. Big Data is not synonymous with data mining, but that’s mostly how it is used for because the people with data mining skills happen to be the people with the ability to process these kinds of data sets – computer and information scientists. I/O could theoretically do a lot of good here with its focus on rigorous construct development, but graduate training (in both I/O and management) is not generally sufficiently grounded in computer programming to get us there just yet. Big Data analysis is not done by clicking buttons in a statistics program. It is done by writing algorithms to process massive data sources, and letting those programs run for days at a time. The closest we get are Monte Carlo simulations. I teach computer programming to our graduate students, but I’m an outlier – it is not (yet) a common skill in I/O. If we want to be on top of Big Data – and of this list, I suspect this is the trend that will stick around the longest – this needs to change.

There you have it. Technology, and the impact of technology, is what current I/O’s are worrying about. It’s a lot of change very quickly, but that just means it’s an especially exciting time to be an I/O psychologist!

![]() From psychology, we’ve known for a while that people create near-instant impressions of people based upon all sorts of cues. Visual cues (like unkempt hair or clothing), auditory cues (like a high- or low-pitched voice), and even olfactory cues (what’s that smell!?!) all combine rapidly to create our initial impressions of a person. Where things get interesting is when one set of these cues is eliminated. For example, if we’ve never met a person in a real life, do we form impressions of people when all we know about them is their Facebook profile? And if so, what do we learn from those profiles?

From psychology, we’ve known for a while that people create near-instant impressions of people based upon all sorts of cues. Visual cues (like unkempt hair or clothing), auditory cues (like a high- or low-pitched voice), and even olfactory cues (what’s that smell!?!) all combine rapidly to create our initial impressions of a person. Where things get interesting is when one set of these cues is eliminated. For example, if we’ve never met a person in a real life, do we form impressions of people when all we know about them is their Facebook profile? And if so, what do we learn from those profiles?

As it turns out, it can be quite a lot. In an upcoming issue of the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Scott1 experimentally examined the impact of viewer gender, Facebook profile gender and number of Facebook friends on impression formation, finding that people with lots of friends appear more socially attractive, more physically attractive, more approachable, and more extroverted.

To determine this, the researcher first conducted a pilot study of 600 existing Facebook profiles (although the source of these profiles is not revealed). From that study, it appears that the researcher extracted wall posts at random to create new profiles, replacing the photo with one drawn from a database of photographs with known attractiveness to a photo of moderate attractiveness (all four within 0.05 SD of each other), updating the number of friends to match the needed condition (90-99 for unpopular and 330-340 for popular), and updating the number of photos to match the needed condition (60-80 for unpopular and 200-250 for popular). This created a database of essentially random Facebook content, although the reason for these particular numbers (or their ranges) was never given.

In the main study, each of 102 undergraduate research participants saw all 4 conditions, in a random order. All participants viewed the profiles on the same computers in the same research laboratory and completed a survey afterwards.

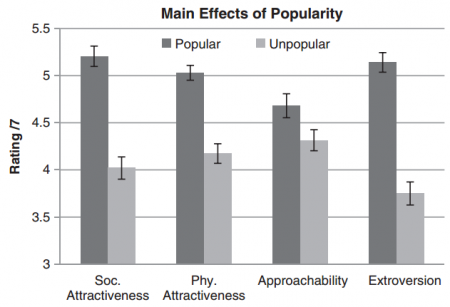

In analyses, neither research participant gender nor profile gender affected any of the five outcomes: social attractiveness, physical attractiveness, approachability, extroversion, and trustworthiness. The only effects found were those from the experimentally controlled popularity manipulation, and these effects were noteworthy.

This figure is a little misleading, since the y-axis doesn’t go down to the bottom of the scale (which was 1), but the effects are still fairly substantial: standard deviations were around 1.2, so these effects range from roughly 0.3 to 1.0 standard deviation – which are moderate to large in magnitude. It is also a little misleading that the trustworthiness outcome is not within the graph, which was assessed but was not statistically significant.

Despite these very small limitations, this study quite cleanly demonstrates that people form a halo of impressions from relatively small cues, just as they do in “real life.” Manipulating only the number of friends and number of posted photos led research participants to view the people behind the profiles as more physically attractive, among other outcomes. This is a critical finding for research examining the value of Facebook profiles and other social media for real-life processes, like hiring or background checks – even relatively small cues can dramatically influence seemingly unrelated judgments made about a person, for better or worse.

- Scott, G. G. (2014). More than friends: Popularity on Facebook and its role in impression formation Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication DOI: 10.1111/jcc4.12067 [↩]