![]() In an upcoming issue of Human Resource Management, Baum and Kabst1 examine the effectiveness of recruitment websites alongside more traditional paper recruitment materials. They conclude that the most effective recruitment is done with a combination of the two.

In an upcoming issue of Human Resource Management, Baum and Kabst1 examine the effectiveness of recruitment websites alongside more traditional paper recruitment materials. They conclude that the most effective recruitment is done with a combination of the two.

To determine this, the researchers sampled 284 German university students, primarily business administration majors, brought into a computer lab. All students were exposed to a recruiting message delivered by a large, multinational organization. They were divided into five groups:

- Group 1 viewed the printed advertisement, then the website.

- Group 2 viewed the website, then the printed advertisement.

- Group 3 viewed only the website.

- Group 4 viewed only the printed advertisement.

- Group 5 viewed neither.

After viewing the recruitment message, the participants completed a variety of surveys. The researchers found:

- Printed advertisements alone did not cause increased knowledge, familiarity, reputation, job information, or attraction.

- Website advertisements alone did cause increased familiarity, reputation, and job information.

- High information recruitment practices (website) have a stronger influence on knowledge and attraction than low information practices (print).

- The use of both print and website together have a stronger effect on knowledge than the main effect of either would predict.

- The use of both print and website together did not have a stronger effect on attraction than the main effect of either would predict.

Although this is an interesting approach, I am not convinced of the authors’ conclusions for three reasons.

First, they used an actual recruitment website and an actual advertisement. Thus, these two media contained different information. The print advertisement only contained testimonials, information about applying, and some general information about the company. The online website contained more in-depth and interactive elements. There is no way to disentangle these effects – the website may have been more effective simply because it contains higher quality information than the print advertisement does. The effect may have been because the website was more “media rich”, or it may have been because the website simply contained more information. We cannot know from this study alone.

Second, the firm was a big, familiar firm to most of the students – this may have introduced an upward bias and/or range restriction among the students – and thus the information contained within the print advertisement may have already been information familiar to most of the participants. Print may be just as effective – or could be more effective – but only if it is equally informative. This is a major confound.

Third, the experiment was conducted on undergraduates sitting in a lab viewing recruitment materials. I’m not as concerned about the use of students for viewing the materials – but there’s a big difference between the motivation of someone sitting in a lab asked to look at recruitment materials for a job in comparison to 1) people flipping casually through a magazine (as if anyone does that anymore) and coming across a job ad or 2) specifically hunting down information on a recruitment website. These are dramatically different situations.

In general, the authors overstate the implications of their study. For example, they concluded, “websites have a significantly stronger impact on employer knowledge than printed advertisements.” Well, maybe. More technically, this particular website designed by a particular well-known organization had a stronger impact than a print advertisement designed by that same organization. There are an awful lot of confounds in this conclusion – with a different website, a different print advertisement, a different industry, a different organizational reputation – these effects may not have appeared. There is absolutely no reason to think that either this print advertisements or this website are representative of print advertisements and websites in general. Interpretation of other observed effects is similarly limited.

When there is a whole universe (statistically speaking) of websites and of print advertisements, finding an effect of one particular website does not demonstrate much.

- Baum, M., & Kabst, R. (2014). The effectiveness of recruitment advertisements and recruitment websites: Indirect and interactive effects on applicant attraction Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm.21571 [↩]

![]() In an upcoming special issue of Social Science Computer Review, Landers and Callan1 set out to understand how people actually use social media while at work and how it affects their job performance. By polling workers across a wide variety of jobs (across at least 17 industries), they identified 8 broad ways that people use social media that they believe help their work, and 9 broad ways that people use social media that they believe harm their work. Although the harmful social media behaviors were related to decreased job performance, the beneficial social media behaviors were unrelated to job performance. In short, wasting time on social media hurts you, but trying to use social media to improve your work probably doesn’t actually help.

In an upcoming special issue of Social Science Computer Review, Landers and Callan1 set out to understand how people actually use social media while at work and how it affects their job performance. By polling workers across a wide variety of jobs (across at least 17 industries), they identified 8 broad ways that people use social media that they believe help their work, and 9 broad ways that people use social media that they believe harm their work. Although the harmful social media behaviors were related to decreased job performance, the beneficial social media behaviors were unrelated to job performance. In short, wasting time on social media hurts you, but trying to use social media to improve your work probably doesn’t actually help.

To conduct this study, the researchers conducted a series of three studies:

- In Study 1, 203 workers across 17 industries provided two critical incidents, one describing a situation where they used social media at work that they believed harmed their job performance, and the other describing a situation where they used social media at work they believed to help their performance. The researchers then conducted a content analysis of these critical incidents to develop 9 “good” behaviors and 9 “bad” behaviors.

- In Study 2, 204 additional workers completed a questionnaire measured the 18 dimensions developed in Study 1. Confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses were used to improve the measurement characteristics of these questionnaires and refine the theoretical model of social media-related behaviors. One of the “good” dimensions, “Relaxation and Leisure” did not load onto a higher-order factor like the other “good” behaviors and was removed from that measure.

- In Study 3, 100 additional workers completed the final questionnaire developed in Study 2 alongside self-report measures of job performance. This provided cross-validation evidence for the measure (reliabilities remained similar between Studies 2 and 3) and also criterion-related validity evidence.

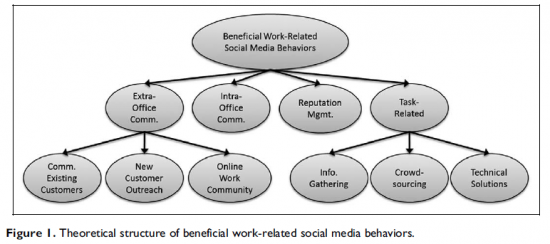

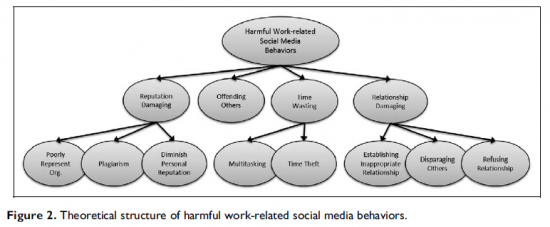

The results of Study 2 (the final social media behavioral taxonomies) are summarized in the following two figures.

Thus, the 8 dimensions of social media behaviors that people think will help their work performance are:

Thus, the 8 dimensions of social media behaviors that people think will help their work performance are:

- Communicating with existing customers

- New customer outreach

- Participating in an online work community

- Intra-office communication

- Reputation management

- Information gathering

- Crowdsourcing a problem

- As the technical solution to a problem (e.g., for file transfer)

Using factor analysis, it was discovered that these 8 dimensions mapped onto four higher-level dimensions:

- Communicating with people outside the office

- Communicating with people inside the office

- Managing the employee’s or the organization’s online reputation

- Trying to solve work problems using social media

The 9 dimensions of social media behaviors that people think harm their work performance are:

- Poorly representing the organization

- Plagiarism or otherwise stealing ideas and representing them as their own

- Reputation-harming behaviors

- Saying something that offends someone

- Multitasking (doing too many things at once)

- Time theft (using social media recreationally on the clock)

- Establishing inappropriate relationships with customers and coworkers

- Making comments that disparage others

- Receiving a friend request, refusing it, and experienced subsequent awkwardness

Using factor analysis again, it was discovered that these 9 dimensions mapped onto four higher-level dimensions:

- Reputation damaging

- Offending others

- Wasting time

- Harming interpersonal relationships

It was in Study 3 that the relationship between the social media behaviors and job performance was determined. Consistently, negative social media behaviors (e.g., plagiarism, mutlitasking, time theft) were correlated with lower job performance (across task, contextual, counterproductive, and adaptive dimensions). But in contrast, positive social media behaviors (e.g., crowdsourcing a problem, identifying new customers) were not generally correlated with job performance at all.

The researcher then make the following practical recommendation:

These findings suggested that simply granting employee access to social media is unlikely to improve job performance unless a specific plan is in place to take advantage of the capabilities it provides. In fact, permitting employee access to social media broadly may be generally harmful to job performance and cannot be recommended based upon these results.

The validation study is somewhat limited in that the job performance measures were self-report, which relies on people’s ability to self-assess their own job performance accurately. Future research should investigate the scale developed here (the Work-Related Social Media Questionnaire [WSMQ]) with more traditional job performance measures (e.g., supervisory ratings).

This study also examines social media behaviors quite broadly; there are probably specific industries or jobs where social media use would be beneficial or even within job requirements. Future research should investigate such positions in particular.

If you’d like to use the WSMQ in your own research, you can find both the beneficial behaviors scale – the WSMQ(+) – and the harmful behaviors scale – the WSMQ(-) – at http://rlnd.us/wsmq.

Also see I/O at Work’s coverage of this article.

- Landers, R.N., & Callan, R.C. (2014). Validation of the Beneficial and Harmful Work-related Social Media Behavioral Taxonomies: Development of the Work-related Social Media Questionnaire Social Science Computer Review DOI: 10.1177/0894439314524891 [↩]

On April 15 at 1PM EDT, I will be giving a webinar on gamification for the Human Capital Institute. If you’re interested in what science says about how gamification and videogames can improve HR processes, you’ll want to be there. Registration is free, but you’ll need to sign up for a free account on the HCI website first. Here’s a bit more detail:

Attract, Assess, and Engage Talent with Gamification

Top firms are utilizing gamification, the use of game playing, thinking and mechanics to engage users and assess capabilities, to improve business results. Spotify replaced their annual reviews with gamification and enjoyed over 90% of their employees participating voluntarily. USA Network was able increase page views by 130% utilizing gamification. (Entrepreneur) Nike, with their fuel band technology, has empowered thousands of people to track and compete with their daily health statistics. How will this technology be used for HR and talent acquisition?

Join this webcast to learn:

- What gamification can do to improve the firm’s online talent community

- How can gamification be used to assess potential talent?

- How does the firm motivate users to participate?

Explore how gaming can encourage passive and active candidates to engage in the firm’s OTC and develop a robust talent pipeline for the future.