![]() When any new technology is introduced purported to “revolutionize teaching,” people tend to get skeptical. Teaching has been the target of revolution many times, yet the best teaching now tends to resemble the best teaching millennia ago, at least at its core. Gamification is one of the more recent approaches, right there alongside MOOCs, tablets, and “modular content.” Gamification’s sudden popularity a few years ago led to everyone to gamify everything they could get their hands on, and it didn’t generally work that well.

When any new technology is introduced purported to “revolutionize teaching,” people tend to get skeptical. Teaching has been the target of revolution many times, yet the best teaching now tends to resemble the best teaching millennia ago, at least at its core. Gamification is one of the more recent approaches, right there alongside MOOCs, tablets, and “modular content.” Gamification’s sudden popularity a few years ago led to everyone to gamify everything they could get their hands on, and it didn’t generally work that well.

Such gamification failures are most directly attributable to this sort of revolution-thinking. A course designer has a technology in hand. The course designer has heard that the technology is GREAT. But the course designer doesn’t actually have a clear reason to adopt it. So the course designer just arbitrarily slaps it on all sorts of situations that don’t make even a little bit of sense, observe that gamification doesn’t accomplish what it was never intended to accomplish, and declare it a failure.

That’s an awful shame to me, because gamification has a great deal of potential not necessarily to revolutionize teaching, but to improve it. To help people realize their educational goals a little less painfully, and perhaps with a little more fun.

In an upcoming issue of Simulation & Gaming, Landers1 presents the Theory of Gamified Learning, which provides a framework by which to deploy gamification successfully in instruction. There are two major ways to do it.

First, gamification efforts can increase a learner behavior or change a learner attitude that we already know is important to learning. For example, we already know that students who take a moment to pause and think about their learning while studying (called meta-cognition) tend to learn more. So a gamification effort targeted at increasing meta-cognition is likely to improve learning. It’s not necessarily going to be transformative or revolutionary or powerful or whatever other gag-inducing word you want to come up with. Instead, it’s quite simple: when we use game elements to help people do what they know they should do anyway, everyone wins.

A great example of this sort of process are gamified fitness apps. Everyone knows they should exercise. We’re bombarded with messages about obesity epidemics and shorter lifespans and all sorts of horrible things. We know this. It’s quite clear at this point – exercise is good for you, vital even. Yet despite that clarity of purpose, it can be quite the fight uphill to drag oneself to the gym. Fitness apps make that a little less of a drag by promising a quick and easy reward/recognition once the workout is complete. It’s not compelling you to act differently. It’s not forcing you to play. It just encourages you to do something that you know you should be doing anyway.

Effective gamification in education that takes this first approach follows the same idea. Effective gamification in education encourages learners to do things they know they should be doing anyway, or perhaps even a step further, it encourages learners to try things they might otherwise be too afraid or indifferent to try.

This is why one of the motivational principles of the Theory of Gamified Learning is that you shouldn’t force learners into participating. Gamification should always recognize and encourage behaviors that are helpful, but not critical. If an activity is critical to learning, it’s not a game. But if it’s something that would be good for learning, game away.

Second, gamification efforts can increase a learner behavior that makes existing instruction more effective. For example, imagine you’ve spent hours developing what is a fabulous set of review questions. You’ve made amazing connections that will make everything so clear! But your learners just aren’t into it. Engagement is low. So we need to increase engagement. This is the process by which review games work – it’s not that the review game itself teaches you anything. Instead, by presenting the review questions as a game, you encourage students to really think about the answers to the questions in a way that they would not otherwise have tried.

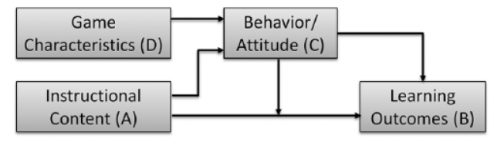

Either approach can be effective. But it must be targeted. You can’t simply throw gamification at learning and hope it to stick. One of these two processes must be targeted, which are summarized in the figure below.

So now that we have a process identified, how do we actually go about gamifying? Fortunately, prior research has already explored which aspects of serious games are typically manipulated in order to influence learning. If our goal is to extract some aspect of these games in order to change something about learners, this sounds like a great place to start. These aspects and examples of gamification appear below. Some of these are likely to work better than others, or in combination. But that is where the research is going next!

| Game Attribute | Definition | Example of Gamification |

| Action Language | The method and interface by which communication occurs between a player and the game itself | To participate in an online learning activity, students are now required to use game console controllers (e.g. a PlayStation controller). |

| Assessment | The method by which accomplishment and game progress are tracked | In a learning activity, points are used to track the number of correct answers obtained by each learner as each learner completes the activity. |

| Conflict/Challenge | The problems faced by players, including both the nature and difficulty of those problems | A small group discussion activity is augmented such that each small group competes for the “best” answer. |

| Control | The degree to which players are able to alter the game, and the degree to which the game alters itself in response | A small group discussion activity is restructured such that each decision made by each small group influences the next topic that group will discuss. |

| Environment | The representation of the physical surroundings of the player | A class meeting is moved from a physical classroom to a 3D virtual world. |

| Game Fiction | The fictional game world and story | Lectures, tests, and discussions are renamed adventures, monsters, and councils, respectively. |

| Human Interaction | The degree to which players interact with other players in both space and time | Learners participate in an online system which reports on their assignment progress to other students as they work. |

| Immersion | The affective and perceptual experience of a game | When learning about oceanography, the walls of the classroom are replaced with monitors displaying real-time images captured from the sea floor. |

| Rules/Goals | Clearly defined rules, goals, and information on progress towards those goals, provided to the player. | When completing worksheet assignments on tablet computers, a progress bar is displayed to indicate how much of the assignment has been completed (but not necessarily the number of correct answers, which would fall under “Assessment”). |

- Landers, R.N. (2015). Developing a Theory of Gamified Learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning Simulation & Gaming DOI: 10.1177/1046878114563660 [↩]

![]() Gamification, the use of game elements in non-game contexts, is increasingly being implemented in both student and organizational learning initiatives. Many of these efforts are atheoretical, meaning that the teachers using them don’t necessarily have a well-grounded reason for gamifying. Instead, they often gamify with the intention of making learning more “fun.”

Gamification, the use of game elements in non-game contexts, is increasingly being implemented in both student and organizational learning initiatives. Many of these efforts are atheoretical, meaning that the teachers using them don’t necessarily have a well-grounded reason for gamifying. Instead, they often gamify with the intention of making learning more “fun.”

Unfortunately, 1) not all gamification is fun and 2) fun is sometimes counterproductive. It is common belief by educators that I’ve spoken with that fun and learning are opposed – as you increase the fun of a learning activity, its impact on learning goes down.

Personally, that doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. Fun and learning should go hand in hand. It seems much more likely that the ways learning activities are being made fun are the problem – not the fun itself.

So if an instructor does want to gamify learning, what theories might be used to guide it? How can gamification be used that won’t potentially harm learning, fun or not?

Recent research by Landers, Bauer, Callan and Armstrong1 sheds some light on this question by exploring several psychological theories of learning in relation to gamification. Specifically, they identify categories of theories that speak to gamification.

- Theory of Gamified Learning. First, and perhaps most relevant, is the theory of gamified learning2. This theory proposes that gamification can affect learning via one of two processes and is intended to guide decision-making when creating gamified activities. Critically to both, gamification should not be intended just to “get people to learn,” and gamification cannot replace high-quality instruction. Instead, it should be targeted at learner behavior and attitudes.

- Gamification can target a behavior or attitude that we already know affects learning. For example, we already know that students who spend more time engaging in meta-cognition (thinking about how they learn) tend to have higher grades. Thus, gamification might be used to increase meta-cognition (e.g., a mobile app might be used to reward students who “check in” to studying).

- Gamification can target a behavior or attitude that makes existing instruction more effective. We might have a great lesson plan to teach oceanography, but students might be bored. To increase their interest, we might bring in an interactive demonstration to illustrate key points. In such cases, the demonstration doesn’t actually teach anything new – it is a type of gamification intended to increase student engagement.

- Conditioning. Classical and operant conditioning are classic psychological theories of learning. Although they have been generally replaced and supplemented with many other theories over the years, they continue to explain a great deal of behavior, especially in children. The most successful type of psychological therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, is even largely based upon operant conditioning principles (the “behavioral” part). At its core, conditioning is quite simple – the goal of the instructor is to create a positive association with a beneficial activity (like studying).

- Expectancy Theories. Expectancy theory is used to describe human motivation. It actually describes three separate motivational processes, listed below. Any particular learning activity can be described as the product of these three processes – if any of the three are low, there will be low motivation.

- Expectancy, which is how likely you believe your actions will lead to a consequence. For example, if I work hard, I’ll score high on the leaderboard.

- Instrumentality, which is how likely you believe that consequence will lead to a reward. For example, if I score high on the leaderboard, I’ll feel good about myself.

- Valence, which is the value you place on that reward. For example, feeling good about myself is very important.

In combination, we might conclude that a leaderboard is likely to be unsuccessful 1) if students don’t think their effort will lead to a high position on the leaderboard, and 2) if students don’t think that a high position on the leaderboard will lead to anything they want.

- Goal-Setting Theory. Goal-setting theory is one of the most well-supported theories of motivation in psychology, and it applies well to learning. People are motivated by SMART goals: specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound. If you incorporate SMART goals in gamification, you are much more likely to get students to do what you want them to do.

- Self-Determination Theory. One of the more recent theories of motivation is self-determination theory, which posits that all humans are motivated by a drive to self-determine – to identify a path for themselves forward through life. This is done by meeting three needs: feeling competent in the tasks you attempt, feeling that you have accomplished those tasks without the influence of others, and feeling that your life is connected to those around you. SDT also defines two types of motivation: intrinsic, which refers to the motivation needs met by satisfaction of those three needs, and extrinsic, which is motivation that is not self-determined. Other-determined motivation is most often considered synonymous with incentives, like gold stars, grades, and recognition from others. Recent work in SDT has revealed that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations work together – that intrinsic motivation occurs when tasks have been internalized, whereas extrinsic motivators are most useful to get people to try new tasks. For example, a person being forced to play piano by a parent might hate it at first but do it anyone to make her parents happy, but later, as she becomes highly competent and autonomous playing, that playing becomes enjoyable on its own. Gamification can be used the same way, to introduce a person to something they don’t have any experience with or know they are good at so that they develop intrinsic motivation later.

Overall, no single theory is going to explain gamification or be the magic bullet for successful gamification. But these theories provide a strong foundation on which to build such efforts.

- Landers, R.N., Bauer, K.N., Callan, R.C., & Armstrong, M.B. (2015). Psychological theory and the gamification of learning Gamification in Education and Business, 165-186 [↩]

- Landers, R. N. (2015). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45, 752-768. [↩]

As is becoming a yearly tradition, the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) has released its list of anticipated top workplace trends for 2015 based upon a vote of the current SIOP membership. Here they are, with a little commentary:

- Changes in Laws May Affect Employment-Related Decisions. This has been a year of sweeping legal changes, most notably Obamacare and recreational marijuana. I guess drug tests don’t mean quite what they did last year.

- Growth of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Programs. There is a growing expectation that organizations must “give back” to the community. This isn’t a new phenomenon, but is becoming more obvious as more Millennials enter the workforce. I know I wouldn’t work for an organization I thought was evil, no matter the salary.

- Changing Face of Diversity Initiatives. Appearing diverse just isn’t enough anymore – people know what a token hire looks like, and they don’t approve. Instead, diversity must be leveraged for an organizational good.

- Emphasis on Recruiting, Selecting for, and Retaining Potential (down from #3 in 2014). In good economies, people like to jump ship, and things are looking pretty good these days. As the effects of the Great Recession continues to dissipate, personnel (industrial) psychologists will be in increasingly high demand; we identify where to look for new talent, how to hire them, and how to keep them.

- Increased Need to Manage a Multi-Generational Workforce. GenX, GenY, Boomers and Silents are all at work now, and GenY just keeps getting bigger. The traditional approach to generational differences (i.e., the older folks lament how useless the new folks are, while the new folks grin and bear it until they’re in control) doesn’t work so well anymore. If your GenY employees don’t like your management, they’re happy to just leave and find a new place to work, finding startups especially attractive. Things are getting complicated.

- Organizations Will Continue to “Do More with Less” (down from #2 in 2014). No surprise here. Bad economies force belt-tightening, and then upper management realizes that belt can stay tight to squeeze even more profit out of the company.

- Increasing Implications of Technology for How Work is Performed (up from #6, #8 and #9 in 2014). Once again, my lab’s specialty gets a prominent place on the list. The Internet of Things, social media, and wearable tech continue to creep into our work lives.

- Integration of Work and Non-Work Life (up from #7 in 2014). Closely related to the item above, technology has made us so connected at all times that it’s difficult to disengage. Is this me writing a blog post at 10PM? Why yes, it is.

- Continued Use of HR Analytics and Big Data (down from #1 in 2014). Big Data is a tricky topic for I/Os, because a lot of I/Os I’ve chatted with like to think that they’ve been doing Big Data for a long time. They haven’t. Big Data is the art and science of identifying, sorting, and analyzing massive sources of data. And I mean massive – a few hundred thousand cases is a bare minimum in my mind. Imagine sticking an RFID chip on every one of your employee’s badges and tracking their movements every day for a year. What might you do with that dataset? That’s Big Data – a little exploratory, a little computer programming, and a lot of potential.

- Mobile Assessments (up from #4 in 2014). The biggest trend this year will be mobile assessments (another of our research areas!). As people increasingly identify and apply for jobs on their phones, their experience is markedly different from that of a desktop or laptop computer. In some cases, they seem to end up with lower scores. The implications of this are only beginning to be understood.

So what else changed from 2014? First, gamification, previously #5 on the list, has dropped off completely. This is probably because gamification has proven to be quite faddish – lots of organizations adopted it without any clue why they were adopting it, and it didn’t do much. In Gartner’s terms, it’s now in the Trough of Disillusionment. But that just means we’re right at the point where reasonable applications of gamification will begin to be discovered. I know I’m doing my part.

Second, several tech-related items all got smushed into #4, which made way for new items on the list – multi-generational issues, law changes, CSR, and diversity.

Looks like an exciting year!