Journal Popularity Among I-O Psychology Academics

As part of a project we completed assessing interdisciplinarity rankings of I-O psychology Ph.D. programs to be published in the next issue of The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist, we created a database containing a list of every paper ever published by anyone currently employed as faculty in an I-O psychology Ph.D. program as recorded in Elsevier’s Scopus database (special thanks to Bo Armstrong, Adrian Helms and Alexis Epps for their work on that project!). Scopus is the most comprehensive database of research output across all disciplines, so that is why we turned to it for our investigation of interdisciplinarity. But the dataset provides a lot of interesting additional opportunities to ask questions about the state of I-O psychology research using publication population data for some field-level self-reflection. No t-tests required when you have population data. I’ve already used the dataset once to very quickly identify which I-Os have published in Science or Nature. The line between self-reflection and naval gazing can be a thin one, and I’m trying to be careful here, but if you have any ideas for further questions that can be answered with these bibliographic data, let me know!

For this first real delve into the dataset, I wanted to explore the relative popularity of I-O psychology’s “top journals.” To get the list of the 8 top journals (and I chose 8 simply because the figure starts to get a bit crowded!), I simply counted how many publications with an I-O psychology faculty member on them appear in each of these journals (you will be able to get more info on this methodology in the TIP article in the next issue along with a list of the top hundred outlets). But importantly, that means my database doesn’t contain two groups of people: I-O practitioners and business school academics. It also doesn’t contain the total number of publications within those journals over years. Those are two important caveats for reasons we’ll get to later.

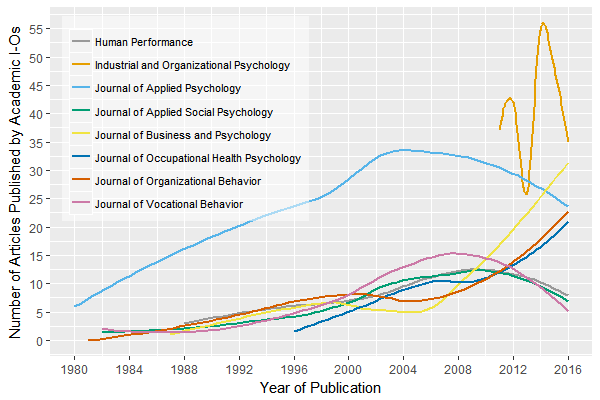

First, I looked at raw publication counts using loess smoothing.

As you can see, the Journal of Applied Psychology has been the dominant outlet for I-O psychology academics for a long time – but that seems to have recently changed. The Journal of Business and Psychology actually published more articles by academic I-O psychologists in 2016 than JAP did. In fact JAP appears to have published fewer and fewer articles by I-Os since around 2001. There are a few potential explanations for this. One, JAP might be published fewer articles in general; two, JAP may be publishing more research by business school researchers instead of I-O academics; three, JAP may be publishing more research by practitioners. I suspect the cause is not option 3.

Also notable is the volatility of Industrial and Organizational Psychology Perspectives, but this is easily attributable to highly varying counts of commentaries considering IOP‘s focal-and-commentary format.

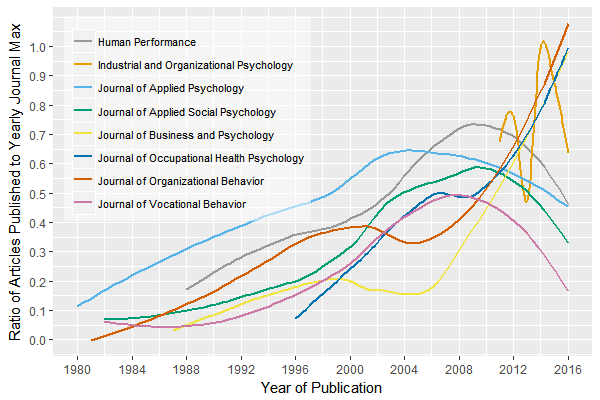

In addition to overall publishing popularity, relative popularity is also of interest. Relative popularity assesses how many academic I-Os have published within a journal relative to each journal’s year with the most I-O publications. This mostly makes change patterns a bit easier to see. This figure appears next.

Of interest here are trajectories. Journals clearly fall into one of three groups:

- Consistency. IOP is the most consistent, as you’d expect; it’s truly the only journal “for I-Os.” Any articles not published by I-O academics are likely published by I-O practitioners.

- Upwards momentum. JBP, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, and Journal of Organizational Behavior all show clear upward trajectories; they are either becoming more popular among I-Os or perhaps simply publishing more work in general with consistent “I-O representativeness” over time. All three published more work by I-O academics in 2015/2016 than they ever have before, as seen in the swing up to 100% at the far right of the figure.

- Decline. JAP, Human Performance, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, and Journal of Vocational Behavior are all decreasing in popularity among academic I-Os. Most journals either maintain their size or increase over time, which suggests that it is popularity with I-O academics in particular that is decreasing. Some of these are more easily explainable than others. JVB for example has been experiencing a long shift back towards counseling psychology over the last decade, which is itself moving even further away from I-O than it already was. Less than half of the editorial board are currently I-Os, and the editor is not an I-O. HP has only been publishing 2 to 5 articles per issue over the last several years, which could reflect either tighter editorial practices or declining popularity in general versus with I-Os. JASP is not really an I-O journal, and I suspect its reputation has likely suffered as the reputation of social psychology in general has suffered due to the replication crisis, but that’s a guess.

To I-Os, JAP is the most interesting of this set and difficult to clearly explain; they still appear to publish the same general number of articles per issue that they have for decades, but from a casual glance, it looks like more business school faculty have been publishing there, which of course also brings “business school values” in terms of publishing – theory, theory, and more theory. This decline among I-Os might also be reflected in its dropping citation/impact rank; perhaps JAP is just not publishing as much research these days that people find interesting, and as a result, I-O faculty are less likely to submit/publish there too. As the face of I-O psychology to the APA and much of the academic world in general, this is worth watching, at the very least.

Completing this analysis helped me realize that something I really want to know is what proportion of publications in all of these journals are not by I-Os. I suspect that the journals that the average I-O faculty member considers “primary outlet for the field” are changing, and that number would help explore this idea.

In the data we already have, there are some other interesting general trends to note; for example, the trajectories of all journals are roughly the same pre-2000. JAP started publishing I-O work a lot earlier than JOB, but their growth curves are very similar after accounting for the horizontal shift in their lines (i.e., their y-intercepts). The most notable changes across all journals occur in 2000 where almost all of the curves are disrupted, with several journals arcing up or down, then again in 2006. The first of these can probably be best explained as “because the internet,” but the cause of the 2006 shifts is unclear to me.

As a side note, this analysis took me a bit under an hour using R from “dataset of 11180 publications” to “exporting figures,” a lot of which was spent making those figures look nice. If you don’t think you could do the same thing in R in under an hour, consider completing my data science for social scientists course, which is free and wraps around interactive online coding instruction in R provided by datacamp.com, starting at “never used R before” and ending with machine learning, natural language processing, and web apps.

| Previous Post: | A Complete Course for Social Scientists on Data Science Using R |

| Next Post: | SIOP 2018: Schedule Planning for IO Psychology Technology |

Surely popularity = being liked or admired. That is, I very much doubt that most IO psychologists like articles published in IOPS or JBP more than articles published in JAP -certainly not as articles listed on their own vitas. The only thing that this really represents to me is that some journals are publishing far more articles than others or that some journals have been taken over by authors from other disciplines (e.g., management) – both factors that you correctly identify.

Another thing that may be going on is that the business schools have effectively captured many (most?) of the top IO faculty so that the remaining faculty in IO PhD programs end up being more “second-tier” and that these authors have greater luck in the less prestigious journals.

I think you are highlighting the very problem; “on their own vitas.” I think people with a goal of publishing in JAP these days are doing so because it is good for their careers, and not because it is good for science, or good for I-O psychology. Management/OB/HR much more directly incentivizes publications in high impact-factor journals, so of course you’re going to see those researchers play to that system as hard as they can. I think I’ve only even submitted two things to JAP in the last 10 years. I just don’t particularly care about journal impact rankings, because I do not see journal impact ranking as synonymous with quality. I know many senior scholars do. And I think that might have been more true in the past. But it is not true now; it is at best correlated, and even then, I suspect not particularly strongly.

I don’t think you can conclude “journals published far more than others” because the trends we are interpreting in are within-journal, over-time. The potential confound is number of articles being published per year fluctuating within journal, but even that to some extent still reflects increased popularity unless you believe those editors are lowering their standards to do so. In most cases, in my experience, that happens because the backlog becomes too large due to increased high-quality submissions, and the editor convinces the publisher that their journal needs to become bigger to accommodate that.

I don’t at all agree that business schools have captured the top IO faculty. I think they have captured the IO faculty that “play the game” most effectively. Again, correlated with quality, but not synonymous.

You write “I don’t at all agree that business schools have captured the top IO faculty. I think they have captured the IO faculty that “play the game” most effectively.” I completely agree with you on this. I am deeply disappointed by much of what is published in our top journals these days and primarily blame the influence of IO psychologists at business schools. Many of our journals have become obsessed with largely meaningless “theory” (as others have documented) which encourages a certain type of analytical approach (mediation, moderation, HLM) and all sorts of questionable research practices (HARKing, Chrysallis Effect, p-hacking, and fabrication).

A few observations:

Interesting data. I must say that I am surprised that Human Performance made the list over OBHDP, or Personnel Psychology. I don’t see evidence for the claim that JVB has become more counseling. By this, do you mean vocational? Even that doesn’t ring true to me. If anything, they seem more open to careers and work/family type research than they used to be. Also, you need to recognize the importance of editorship on some of the trends. JASP had Andrew Baum for many years. He was much more favorable to organizational research than is the current editor. Also, the JBP editor has played the game hard. Nearly every psychology faculty in an IO program is on his editorial board (just look). He throws big parties at SIOP, invites highly-citable methods pieces, and encourages self-citation (despite his own admonitions).

Yes, I do mean vocational, i.e., vocational counseling. For example, here is the April 2018 JVB issue, which is on refugees. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-vocational-behavior/vol/105

I’m not saying that such topics are not I/O-relevant, but they are definitely not “core I-O”. A lot of the work-family research has moved more toward an interdisciplinary perspective. Frankly, I think that’s a good thing – but it does mean that there is less “mainstream I-O” published there now than in the past.

I agree re: editorship, but journals last beyond editors and those reputations persist. JBP is actually a great example of this; the editor has made a lot of effective choices in terms of creating community and positioning his journal to be at the core of the field. I feel like you are saying “big parties” is by definition a negative, but it does engage the human aspect of science directly, and that sort of thing is critical in terms of getting a group of people to trust each other. Maybe not parties per se – but something.

I’m not sure if you are saying “highly-citable methods pieces” is a negative too, but that would not be reflected in these data except indirectly anyway; it might increase impact factor, but JBP’s impact factor is still lower than JAP’s, so you would not expect the pattern reversal seen here from that alone. I suppose you could claim that JBP has engaged in practices to increase its impact factor, and that impact factor has encouraged more people to publish there, but frankly its impact factor increase has only been in the last 2-3 years, so you would not expect people submitting to be influenced by that until the last year or two, at earliest. This appears to be a longer-term trend.

You sound a bit defensive of JOBP. Have you looked at the editorial board? Seems like it is an attempt to make sure all IO people attend the board party. Not what journals are meant to be. More an attempt at self-adoration. #narcissistseemlikeawesomepeoplewhenyouonlyseethemonceayear

I’m not sure where you would get that. I just admire what he’s trying to do with it re: its initiatives, and in my judgment, they are mostly “good” ideas. Your comment sounds a little more… personal.

Also, I’m not sure what you mean by “not what journals are meant to be.” I suppose I thought of journals as a community of scholars coming together with a shared purpose and building new knowledge together. Do you have another definition? What are journals meant to be, in terms of editorial boards, and where do you get your definition?

I don’t know you, but I suspect you don’t see yourself as prone to cult membership. If you examine the characteristics of cults, however, I think you would see some resemblance.