Examining Evidence for Leaderboards and Learning

![]() As I described in my last post, gamification is often misused and abused, applied in ways and in situations where it is unlikely to do much good. When we deploy new learning technologies, the ultimate goal of that change should always be clear, first and foremost. So how do you actually go about setting that sort of goal? In an upcoming issue of Simulation & Gaming, Landers and Landers1 experimentally evaluate the Theory of Gamified Learning to explore not only how leaderboards can be used to improve learning but also to demonstrate the decision-making process that you should engage in before trying them out. This is important, because leaderboards are one of the more contested tools in the gamification toolkit.

As I described in my last post, gamification is often misused and abused, applied in ways and in situations where it is unlikely to do much good. When we deploy new learning technologies, the ultimate goal of that change should always be clear, first and foremost. So how do you actually go about setting that sort of goal? In an upcoming issue of Simulation & Gaming, Landers and Landers1 experimentally evaluate the Theory of Gamified Learning to explore not only how leaderboards can be used to improve learning but also to demonstrate the decision-making process that you should engage in before trying them out. This is important, because leaderboards are one of the more contested tools in the gamification toolkit.

On one hand, they are one of the oldest and still most common forms of gamification across contexts, including the learning context. If you’re over about 25, you probably remember a high school teacher or college professor posting grades outside the classroom with your name and your grade. That’s a leaderboard. We’ve been using them to motivate students for a very long time, although the way we use them has been changing recently.

On the other hand, leaderboards are often considered by gamification practitioners with the term PBL: points, badges, and leaderboards. PBL is often used disparagingly to refer to the most overused of all tools in the gamification toolkit. They are overused because they are the easiest to implement; PBL can be applied just about any situation, even if there’s not really a good reason to do so.

In their paper, the researchers followed the story of a course with a problem that gamification was used to solve. In this course, a semester-long project was assigned on a wiki. The goal of this project was for students to conduct independent research on an assigned topic and write a wiki article about their topic. The hope of the instructor for this project was that students would engage with the wiki project throughout the semester, learning along the way. Unfortunately, as any course instructor knows, students tend to procrastinate. In looking at usage data from past semester, the instructor realized that most of the class would only work on the project the week before it was due.

Given this, the instructor turned to the theory of gamified learning to identify what type of gamification would be best to increase the amount of time students spent working on their project. Leaderboards were chosen because they were persistent throughout the entire semester and could be used to provide very clear, well-defined goals related to the amount of time spent working on the project.

If you’ve taken a look at theory of gamified learning, you’ll recognize this as a gamification effort that can increase a learner behavior or change a learner attitude that we already know is important to learning. We already know that spending more time on an assignment is good for learning! That means the next step is to find a gamification technique that will increase that amount of time.

To test if this actually happened, the researchers randomly split the course in half and assigned the halves to either a wiki gamified with a leaderboard or a wiki without a leaderboard. This experimental design was important in order to conclude that the leaderboard actually caused changes in learning. The results of this study revealed that this approach worked just as expected. In statistical terms, the amount of time spent on the project mediated the relationship between gamification and project scores. On average, students experiencing leaderboards made 29.61 more edits to their project than those without leaderboards.

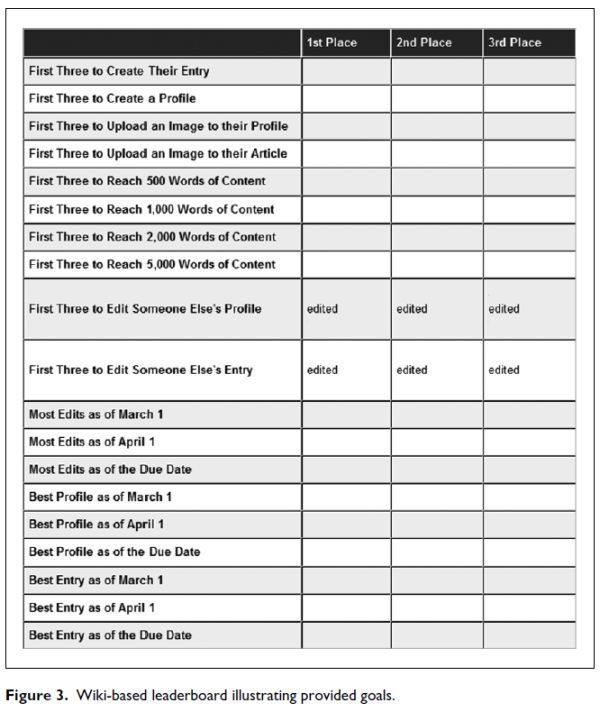

In actually implementing the leaderboard, two sets of decisions were key. First, all entries on the leaderboard were specifically targeted at increasing the amount of time spent on the leaderboard, which was the focal behavior chosen before the project began. For example, several leaderboard items tracked who had edited their entry the most times as of multiple time points in the course – after one month, after two months, and by the end of the course.

Second, the leaderboard was optional. Key to all gamification efforts is that participants must feel that they have a choice to participate. Just like organizational citizenship behaviors, once you require participation in a game, it’s no longer a game. The same applies to gamification. None of the tasks on the leaderboard were explicitly required to earn a high grade; instead, they simply encouraged students to focus their attention and return frequently to their project, as shown below.

It’s important to be very clear that this project does not demonstrate that leaderboards always benefit learning. Instead, leaderboards are just one example of the many tools available to gamification designers that can be used depending upon the specific goal of gamification. This time it was leaderboards; next time, it may be action language or game fiction. The key takeaway is that you need to decide exactly what you’re trying to change before you dive into choosing your game elements, and then choose an element to meet your instructional goals.

- Landers, R., & Landers, A. (2015). An Empirical Test of the Theory of Gamified Learning: The Effect of Leaderboards on Time-on-Task and Academic Performance Simulation & Gaming DOI: 10.1177/1046878114563662 [↩]

| Previous Post: | How to Gamify Your Teaching: The Processes of Gamification |

| Next Post: | Top 20 Most Prolific Presenters at SIOP 2015 |

Hi,

Helpful article including handy key take aways.

Is it possible to share some examples of the tasks mentioned in the following statement (extracted from the article above)in particular tasks that encouraged them to return frequently.

None of the tasks on the leaderboard were explicitly required to earn a high grade; instead, they simply encouraged students to focus their attention and return frequently to their project.

Thanks

Sonia

Good point! I’ve added a screenshot of the leaderboard to the main article. For this leaderboard, being in the “top 3” of anything was not necessary in order to get a higher grade, profile quality did not affect grades in any way, and there were no article length requirements. Hope that helps!

Great article. I am wondering about the quantitative research on the topic of the theory of gamification. Are there studies?

Many, including the one discussed here.

Thanks for this article! Was the leaderboard automatically populated or did the instructor have to input that information?

It was all instructor updated, although with the right infrastructure, most of it could have been automated!