How to Gamify Your Teaching: The Processes of Gamification

![]() When any new technology is introduced purported to “revolutionize teaching,” people tend to get skeptical. Teaching has been the target of revolution many times, yet the best teaching now tends to resemble the best teaching millennia ago, at least at its core. Gamification is one of the more recent approaches, right there alongside MOOCs, tablets, and “modular content.” Gamification’s sudden popularity a few years ago led to everyone to gamify everything they could get their hands on, and it didn’t generally work that well.

When any new technology is introduced purported to “revolutionize teaching,” people tend to get skeptical. Teaching has been the target of revolution many times, yet the best teaching now tends to resemble the best teaching millennia ago, at least at its core. Gamification is one of the more recent approaches, right there alongside MOOCs, tablets, and “modular content.” Gamification’s sudden popularity a few years ago led to everyone to gamify everything they could get their hands on, and it didn’t generally work that well.

Such gamification failures are most directly attributable to this sort of revolution-thinking. A course designer has a technology in hand. The course designer has heard that the technology is GREAT. But the course designer doesn’t actually have a clear reason to adopt it. So the course designer just arbitrarily slaps it on all sorts of situations that don’t make even a little bit of sense, observe that gamification doesn’t accomplish what it was never intended to accomplish, and declare it a failure.

That’s an awful shame to me, because gamification has a great deal of potential not necessarily to revolutionize teaching, but to improve it. To help people realize their educational goals a little less painfully, and perhaps with a little more fun.

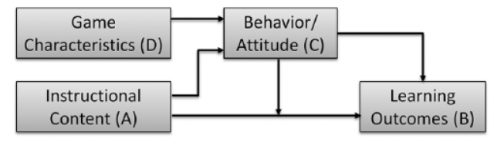

In an upcoming issue of Simulation & Gaming, Landers1 presents the Theory of Gamified Learning, which provides a framework by which to deploy gamification successfully in instruction. There are two major ways to do it.

First, gamification efforts can increase a learner behavior or change a learner attitude that we already know is important to learning. For example, we already know that students who take a moment to pause and think about their learning while studying (called meta-cognition) tend to learn more. So a gamification effort targeted at increasing meta-cognition is likely to improve learning. It’s not necessarily going to be transformative or revolutionary or powerful or whatever other gag-inducing word you want to come up with. Instead, it’s quite simple: when we use game elements to help people do what they know they should do anyway, everyone wins.

A great example of this sort of process are gamified fitness apps. Everyone knows they should exercise. We’re bombarded with messages about obesity epidemics and shorter lifespans and all sorts of horrible things. We know this. It’s quite clear at this point – exercise is good for you, vital even. Yet despite that clarity of purpose, it can be quite the fight uphill to drag oneself to the gym. Fitness apps make that a little less of a drag by promising a quick and easy reward/recognition once the workout is complete. It’s not compelling you to act differently. It’s not forcing you to play. It just encourages you to do something that you know you should be doing anyway.

Effective gamification in education that takes this first approach follows the same idea. Effective gamification in education encourages learners to do things they know they should be doing anyway, or perhaps even a step further, it encourages learners to try things they might otherwise be too afraid or indifferent to try.

This is why one of the motivational principles of the Theory of Gamified Learning is that you shouldn’t force learners into participating. Gamification should always recognize and encourage behaviors that are helpful, but not critical. If an activity is critical to learning, it’s not a game. But if it’s something that would be good for learning, game away.

Second, gamification efforts can increase a learner behavior that makes existing instruction more effective. For example, imagine you’ve spent hours developing what is a fabulous set of review questions. You’ve made amazing connections that will make everything so clear! But your learners just aren’t into it. Engagement is low. So we need to increase engagement. This is the process by which review games work – it’s not that the review game itself teaches you anything. Instead, by presenting the review questions as a game, you encourage students to really think about the answers to the questions in a way that they would not otherwise have tried.

Either approach can be effective. But it must be targeted. You can’t simply throw gamification at learning and hope it to stick. One of these two processes must be targeted, which are summarized in the figure below.

So now that we have a process identified, how do we actually go about gamifying? Fortunately, prior research has already explored which aspects of serious games are typically manipulated in order to influence learning. If our goal is to extract some aspect of these games in order to change something about learners, this sounds like a great place to start. These aspects and examples of gamification appear below. Some of these are likely to work better than others, or in combination. But that is where the research is going next!

| Game Attribute | Definition | Example of Gamification |

| Action Language | The method and interface by which communication occurs between a player and the game itself | To participate in an online learning activity, students are now required to use game console controllers (e.g. a PlayStation controller). |

| Assessment | The method by which accomplishment and game progress are tracked | In a learning activity, points are used to track the number of correct answers obtained by each learner as each learner completes the activity. |

| Conflict/Challenge | The problems faced by players, including both the nature and difficulty of those problems | A small group discussion activity is augmented such that each small group competes for the “best” answer. |

| Control | The degree to which players are able to alter the game, and the degree to which the game alters itself in response | A small group discussion activity is restructured such that each decision made by each small group influences the next topic that group will discuss. |

| Environment | The representation of the physical surroundings of the player | A class meeting is moved from a physical classroom to a 3D virtual world. |

| Game Fiction | The fictional game world and story | Lectures, tests, and discussions are renamed adventures, monsters, and councils, respectively. |

| Human Interaction | The degree to which players interact with other players in both space and time | Learners participate in an online system which reports on their assignment progress to other students as they work. |

| Immersion | The affective and perceptual experience of a game | When learning about oceanography, the walls of the classroom are replaced with monitors displaying real-time images captured from the sea floor. |

| Rules/Goals | Clearly defined rules, goals, and information on progress towards those goals, provided to the player. | When completing worksheet assignments on tablet computers, a progress bar is displayed to indicate how much of the assignment has been completed (but not necessarily the number of correct answers, which would fall under “Assessment”). |

- Landers, R.N. (2015). Developing a Theory of Gamified Learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning Simulation & Gaming DOI: 10.1177/1046878114563660 [↩]

| Previous Post: | Psychological Theory and Gamification of Learning |

| Next Post: | Examining Evidence for Leaderboards and Learning |

I have sent you a message through Linkedin. We share a common interest in Gamification, though you have done a lot of research, and I am just looking at it as an area of interest, though I have done a lot of experimentation in my classes which is often drawn and inspired from my interest in game design. So I though of collaborating occured to me.

Regards

Vineet

Oh and yes, what a scholar! he looks so trustworthy!