Is Outrage Over the Facebook Mood Manipulation Study Anti-Science or Ignorance?

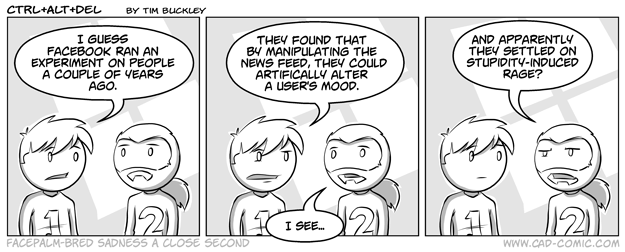

![]() By now, you’ve probably heard about the latest controversy coming from Facebook – a researcher internal to Facebook, along with two university collaborators, recently published a paper in PNAS1 that included an experimental manipulation of mood. Specifically, the researchers randomly assigned about 700,000 Facebook users to test an interesting causal question: does the emotional content of posts read on Facebook alter people’s moods?

By now, you’ve probably heard about the latest controversy coming from Facebook – a researcher internal to Facebook, along with two university collaborators, recently published a paper in PNAS1 that included an experimental manipulation of mood. Specifically, the researchers randomly assigned about 700,000 Facebook users to test an interesting causal question: does the emotional content of posts read on Facebook alter people’s moods?

This is an interesting and a compelling way to study that question. Research to this point has focused on scouring pre-existing news feeds and inferring emotion from posted content. This has led to some other well-known Facebook research about the Facebook envy spiral, in which people post exaggerated accounts of the positive events in their lives, which leads reading users to become jealous and post even more exaggerated accounts of their own lives. In the end, on Facebook, everyone else looks like they’re doing better than you. The downside of this focus on pre-existing news is that it’s impossible to demonstrate causality – we don’t know that viewing content on Facebook actually causes you to think or behave differently. To demonstrate causation (not just correlation), you need an experiment, and that’s exactly what these researchers did. The result? Manipulating viewed post mood did affect the apparently mood in posts made by the study participants – but the effect was tiny (d = 0.02 was the largest observed effect). So it makes a difference – but perhaps not as big of one as previous research has suggested.

Reactions have been mixed. Psychologists and science writers have tended to focus on explaining the study to non-psychologists, whereas popular sources have focused (as usual) on the outrage.

With that, we come to the heart of my title-question: Is the outrage over the Facebook mood manipulation study mere ignorance or anti-science? Let me explain with three points.

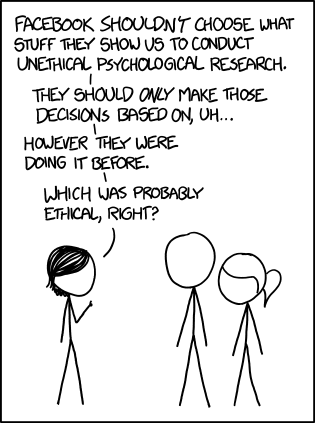

First, we know that web media companies, especially those who have hired marketing consultants, engage in internal experimental research with our data and our moods all the time. They do this to improve the attractiveness of their products. By randomly assigning people viewing web content to two different experiences, they can observe the difference between the two in terms of time spent on the site, information shared, and a variety of other metrics. Data in hand, web developers can then change their entire site to the format that was most successful in experimental testing. Websites like Amazon, Yelp, and Facebook all do this with user-contributed data, altering the algorithms that shape what you see. Even Wikipedia’s example of this approach involves randomly assigning people to receive different marketing emails. For people that didn’t know this approach was so common, despite agreeing to Facebook’s terms of service that indicate your permission for them to experiment on you freely, their outrage is likely driven by ignorance. I suggest these people go delete their Facebook accounts right now, or at least read the terms of service more carefully.

Second, if you are aware that Facebook is collecting your data and manipulating you, but you didn’t find the Facebook experience to be worth that loss of data control, you should have also deleted your account by now. As Facebook is a private company with a product they are trying to sell you, you are perfectly free to give up on that product at will. You can’t be mood-manipulated if you don’t use their service. If you’re angry and haven’t deleted your account, you have already, through your actions, demonstrated that access to Facebook is more important to you than avoiding being manipulated by a massive technology company.

Third, if you already knew that Facebook was collecting your data and manipulating you, the major difference with this study and the hundreds of studies that Facebook has undoubtedly already done is that it is published in the scientific research literature. Most research like this goes on behind closed doors. You know that Big Data is processing all of the status updates that you provide to Facebook and that experimental manipulations are being used to compel you to stare at Facebook longer. But this time, they went public with the results – and only now is there anger.

Having said all that, could the researchers have handled this better to minimize negative public reactions? Certainly yes.

First, obtaining informed consent from participants that an experiment was going on would undoubtedly have biased their results, so obtaining consent ahead of time would not have been possible – a justifiable risk, given the exceptionally low probability of harm (in the terms of IRB, “minimal risk”) to participants in this study. However, it would have been courteous to have either debriefed participants (even now, we don’t know exactly who was manipulated) or given participants the opportunity to withhold their data from the final dataset, even if users have explicitly agreed to be experimented on in their day-to-day interactions on Facebook.

Second, the ethical review process for this study was business-as-usual for many IRBs – in other words, orchestrated by the researchers to minimize the hassle they needed to go through to meet the minimum possible institutional requirements for that review. Facebook apparently conducted an internal review of the study protocol proposed by the first author (a Facebook employee), presumably in consultation with his two Cornell faculty co-authors. No surprises there – Facebook manipulates its users all the time, this manipulation was within its terms of service, so why would they care? Once the data were collected, the Cornell faculty authors applied to their own IRB to use the data collected by Facebook as “pre-existing data.” Given the sheer scope of this study, knowing that they’d be trying to alter the interactions of three-quarters of a million people, the faculty would have been better off sending the study for full IRB review. Having said that, a full IRB probably would have approved the protocol anyway because the manipulation was well in line with what Facebook already does on a regular basis anyway – the researchers just redirected Facebook’s business-as-usual to conduct science instead of, or perhaps in addition to, profit.

- Kramer, A., Guillory, J., & Hancock, J. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111 (24), 8788-8790 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1320040111 [↩]

| Previous Post: | SIOP 2014: Reflections on SIOP Honolulu |

| Next Post: | How to Write a Publishable Social Scientific Research Article: Exploring Your “Process” |