Multiplayer Really Is More Fun: New Research

![]() Most academic research on video games studies them as single player experiences – a single individual, alone in a room with a game console. Study on massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs) is also growing. However, much (and perhaps most) video game play in the modern day is multiplayer in a smaller setting: or at home in front of a Kinect or a Wii with two or three friends. Surprisingly little research has examined this context.

Most academic research on video games studies them as single player experiences – a single individual, alone in a room with a game console. Study on massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs) is also growing. However, much (and perhaps most) video game play in the modern day is multiplayer in a smaller setting: or at home in front of a Kinect or a Wii with two or three friends. Surprisingly little research has examined this context.

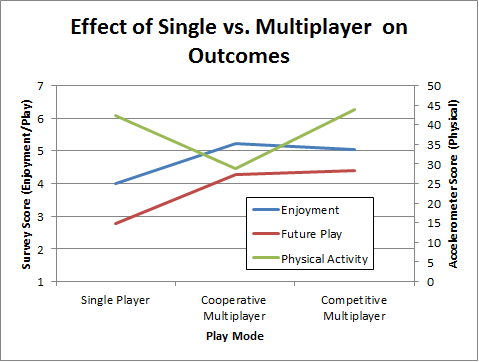

In a recent issue of Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Newtorking, Peng and Crouse1 compared enjoyment, future play motivation and physical intensity on XBOX 360 game Kinect Adventures between single player, cooperative multiplayer and competitive multiplayer modes, finding that competitive multiplayer provided the greatest enjoyment, motivation to play in the future, and physical activity.

The highly physical core game mechanic is best described by the authors:

This game utilized the Kinect motion camera, and the players used their own bodies as the controller to pop soap bubbles that floated between holes on the walls, floors, and ceilings of a virtual zero-gravity room by moving forward, backward, left, and right and waving their arms.

These three conditions were more complex than they appear:

- In the single player condition, participants played alone, twice. In this way, they were competing with their pre-test score.

- In the cooperative mutliplayer condition, participants brought a friend. After individual pre-tests, the two participants next played the game with each other (they were physically active in the same space simultaneously and their scores were combined).

- In the competitive multiplayer condition, participants brought a friend. After individual pre-tests, the two participants then played the game separately (in different rooms) and were told what their friend’s previous high score was on the pre-test.

After the game, participants completed the focal measures. Enjoyment was assessed with a 7-item scale asking them to rate the game on seven adjectives (including “boring,” “entertaining,” and “interesting”). Future play intention was rated on a 3-item scale asking questions like, “Given the chance, I would play this game in my free time.” Physical activity was captured with an accelerometer attached to each player.

162 students participated in the study; however, this seems to include the friend counts. Sample sizes were 26 for single player, 74 for cooperative play and 52 for competitive play. Given that their analytic strategy was a simple ANOVA, it does not seem that the researchers appropriately controlled for covariance between friend pairs – a better strategy would have been to have not included the “friend” in analysis, however this would have dropped their apparent (although misleading) reported sample size.

Based upon the reported ANOVA, several were statistically significant. Single player enjoyment was lower than cooperative and competitive multiplayer modes. Future play motivation after playing alone was lower than both cooperative and competitive mutliplayer modes. For physical activity, the relationship was more complicated. In this case, the single player and cooperative mutliplayer modes resulted in greater physical activity than the competitive multiplayer.

The authors did not depict these relationship graphically (always graph your results!), so I did:

Although the affects appear pretty substantial in terms of effect size (for example, from 3.99 to 5.22 for enjoyment, about 0.8 standard deviations), it’s hard to say how much the double-sample for the two multiplayer modes inflated the F-statistics (and thus statistical significance) of the results. So I am not 100% confident in the researchers’ interpretation of these data, but I am cautiously optimistic that these results would hold up with appropriate consideration of dependence.

In the context of education and training, this has some critical implications: play with others seems preferable to play alone. While this might seem intuitive, we too often build serious games and gamification efforts where people compete against themselves (e.g. high scores, or some instructor-set target goal level). Adding some coworkers or fellow students to the mix might just improve those efforts.

- Peng, W., & Crouse, J. (2013). Playing in parallel: The effects of multiplayer modes in active video game on motivation and physical exertion Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0384 [↩]

| Previous Post: | Textual Harassment at Work: Romance and Sexual Harassment on Social Media |

| Next Post: | SIOP 2013: Schedule Planning |

I recently read an article in Runner’s World magazine summarizing a study (I have yet to read the primary source) from the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology related to competitiveness and performance (http://www.runnersworld.com/sports-psychology/study-rivalry-can-boost-performance).

While the interpersonal component of manipulation is different for the JESP piece (manipulation of feedback type and feedback source [ingroup vs. outgroup]) it made me think about the physical activity findings for this study.

It seems that, for this particular task, there is something beneficial about the concept of competition. Although I am not familiar with the game, I would assume that level of physical activity is likely related to performance (I could be wrong). Thus, it seems as if competitiveness might actually be beneficial for this MMOG. However, not knowing if there was a main effect of group for physical activity (and because I am unfamiliar with Kinect Adventures), I cannot be certain. The odd part is that individuals who competed as a single player seemed (at least graphically) to exert themselves just as much as individuals in the competitive group, whereas the cooperative group had the lowest levels of physical activity.

I think an most important finding is the level of future play. The last thing that trainers and ISD folks should want to do is create a training paradigm which elicits the trainee response of, “Well I never want to do that again…”

In post hoc tests, the differences I described above were statistically significant (single vs coop, coop vs. competitive, no others). The nature of the game might be key to the effect – you are correct that increased physical activity is related to increased performance. But in cooperative multiplayer in Kinect games, the game environment is quite different from the other two because you can literally smack your friend next to you if you flail too wildly. So this may have inhibited their performance in the cooperative condition in a way that would not have occurred in the other two conditions.