Even If Job Applicants Cheat, Online Testing May Still Increase Job Performance

![]() When hiring with online tests (a concept called unproctored internet testing [UIT]), one of the biggest worries is that test-takers will cheat. A home computer is just about as “unsecured” a testing environment as possible, so test-takers have many options to deceive their potential employers: looking up answers on the Internet or getting a friend to complete the test for them are just two options. When people cheat, their test scores no longer represent their ability level, which reduces the average job performance of those that ultimately get hired. One remedy for this is something called “verification testing,” where job candidates are re-tested at a later stage of the selection process: for example, they might complete an intelligence test online and, after passing it, take a parallel version of that test in person. But many organizations don’t want the extra hassle of verification testing, because it takes more time and effort on the part of both the organization and the job candidate. So if people are cheating, can the organization still come out ahead by using online testing?

When hiring with online tests (a concept called unproctored internet testing [UIT]), one of the biggest worries is that test-takers will cheat. A home computer is just about as “unsecured” a testing environment as possible, so test-takers have many options to deceive their potential employers: looking up answers on the Internet or getting a friend to complete the test for them are just two options. When people cheat, their test scores no longer represent their ability level, which reduces the average job performance of those that ultimately get hired. One remedy for this is something called “verification testing,” where job candidates are re-tested at a later stage of the selection process: for example, they might complete an intelligence test online and, after passing it, take a parallel version of that test in person. But many organizations don’t want the extra hassle of verification testing, because it takes more time and effort on the part of both the organization and the job candidate. So if people are cheating, can the organization still come out ahead by using online testing?

In an upcoming article in the International Journal of Selection and Assessment, Landers and Sackett1 simulate the conditions under which mean job performance of those hired will be different when job applicants are cheating. This includes both positive and negative changes to job performance, relative to the selection system used before UIT was adopted. The key is recruitment; if online testing enabled an organization to reach a large pool of applicants, it can be more selective, improving mean job performance.

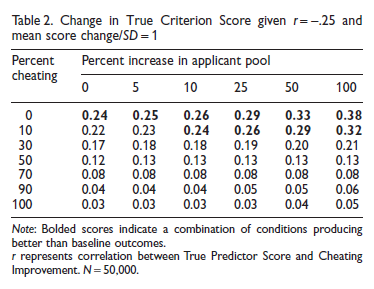

You can see a sample of the researchers’ findings in the table here. The top left corner (0.24) represents the baseline. With the criterion-related validity chosen for simulation, job performance is 0.24 standard deviations higher than the previous system when no one is cheating and the applicant pool is not increased. We can compare the other values in the table to this baseline. For example, if 10% of your applicant pool is cheating but you double the size of your applicant pool, online testing results in a job performance level of 0.32 (over a 33% increase in job performance!). However, if 50% of your applicant pool is cheating, doubling the applicant pool will result in lower job performance over your old system (about a 46% decrease!).

Perhaps more disturbingly, some simulation conditions resulted in not only lower than baseline job performance but negative job performance. In other words, under some conditions, using online testing resulted in lower job performance than hiring at random.

This points to a pressing need for future research to identify what percentage of applicants we would expect to cheat and other simulation parameters. Unfortunately, dishonest behavior is one of the most difficult areas of study in psychological research. While in most studies, the biggest concern in this area is participant apathy (i.e. bored undergraduates not paying attention), people are outright working against you when trying to determine how dishonest they are. We can only hope this research spurs further work in this area.

- Landers, R. N., & Sackett, P. R. (2012). Offsetting performance losses due to cheating in unproctored Internet-based testing by increasing the applicant pool. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 20 (2), 220-228. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2012.00594.x [↩]

| Previous Post: | High Citation Counts Don’t Mean Scholarly Work is Impactful |

| Next Post: | Summer 2012 Updates and Posting Schedule |