Computing Intraclass Correlations (ICC) as Estimates of Interrater Reliability in SPSS

If you think my writing about statistics is clear below, consider my student-centered, practical and concise Step-by-Step Introduction to Statistics for Business for your undergraduate classes, available now from SAGE. Social scientists of all sorts will appreciate the ordinary, approachable language and practical value – each chapter starts with and discusses a young small business owner facing a problem solvable with statistics, a problem solved by the end of the chapter with the statistical kung-fu gained.

If you think my writing about statistics is clear below, consider my student-centered, practical and concise Step-by-Step Introduction to Statistics for Business for your undergraduate classes, available now from SAGE. Social scientists of all sorts will appreciate the ordinary, approachable language and practical value – each chapter starts with and discusses a young small business owner facing a problem solvable with statistics, a problem solved by the end of the chapter with the statistical kung-fu gained.

This article has been published in the Winnower. You can cite it as:

Landers, R.N. (2015). Computing intraclass correlations (ICC) as estimates of interrater reliability in SPSS. The Winnower 2:e143518.81744. DOI: 10.15200/winn.143518.81744

You can also download the published version as a PDF by clicking here.

![]() Recently, a colleague of mine asked for some advice on how to compute interrater reliability for a coding task, and I discovered that there aren’t many resources online written in an easy-to-understand format – most either 1) go in depth about formulas and computation or 2) go in depth about SPSS without giving many specific reasons for why you’d make several important decisions. The primary resource available is a 1979 paper by Shrout and Fleiss1, which is quite dense. So I am taking a stab at providing a comprehensive but easier-to-understand resource.

Recently, a colleague of mine asked for some advice on how to compute interrater reliability for a coding task, and I discovered that there aren’t many resources online written in an easy-to-understand format – most either 1) go in depth about formulas and computation or 2) go in depth about SPSS without giving many specific reasons for why you’d make several important decisions. The primary resource available is a 1979 paper by Shrout and Fleiss1, which is quite dense. So I am taking a stab at providing a comprehensive but easier-to-understand resource.

Reliability, generally, is the proportion of “real” information about a construct of interest captured by your measurement of it. For example, if someone reported the reliability of their measure was .8, you could conclude that 80% of the variability in the scores captured by that measure represented the construct, and 20% represented random variation. The more uniform your measurement, the higher reliability will be.

In the social sciences, we often have research participants complete surveys, in which case you don’t need ICCs – you would more typically use coefficient alpha. But when you have research participants provide something about themselves from which you need to extract data, your measurement becomes what you get from that extraction. For example, in one of my lab’s current studies, we are collecting copies of Facebook profiles from research participants, after which a team of lab assistants looks them over and makes ratings based upon their content. This process is called coding. Because the research assistants are creating the data, their ratings are my scale – not the original data. Which means they 1) make mistakes and 2) vary in their ability to make those ratings. An estimate of interrater reliability will tell me what proportion of their ratings is “real”, i.e. represents an underlying construct (or potentially a combination of constructs – there is no way to know from reliability alone – all you can conclude is that you are measuring something consistently).

An intraclass correlation (ICC) can be a useful estimate of inter-rater reliability on quantitative data because it is highly flexible. A Pearson correlation can be a valid estimator of interrater reliability, but only when you have meaningful pairings between two and only two raters. What if you have more? What if your raters differ by ratee? This is where ICC comes in (note that if you have qualitative data, e.g. categorical data or ranks, you would not use ICC).

Unfortunately, this flexibility makes ICC a little more complicated than many estimators of reliability. While you can often just throw items into SPSS to compute a coefficient alpha on a scale measure, there are several additional questions one must ask when computing an ICC, and one restriction. The restriction is straightforward: you must have the same number of ratings for every case rated. The questions are more complicated, and their answers are based upon how you identified your raters, and what you ultimately want to do with your reliability estimate. Here are the first two questions:

- Do you have consistent raters for all ratees? For example, do the exact same 8 raters make ratings on every ratee?

- Do you have a sample or population of raters?

If your answer to Question 1 is no, you need ICC(1). In SPSS, this is called “One-Way Random.” In coding tasks, this is uncommon, since you can typically control the number of raters fairly carefully. It is most useful with massively large coding tasks. For example, if you had 2000 ratings to make, you might assign your 10 research assistants to make 400 ratings each – each research assistant makes ratings on 2 ratees (you always have 2 ratings per case), but you counterbalance them so that a random two raters make ratings on each subject. It’s called “One-Way Random” because 1) it makes no effort to disentangle the effects of the rater and ratee (i.e. one effect) and 2) it assumes these ratings are randomly drawn from a larger populations (i.e. a random effects model). ICC(1) will always be the smallest of the ICCs.

If your answer to Question 1 is yes and your answer to Question 2 is “sample”, you need ICC(2). In SPSS, this is called “Two-Way Random.” Unlike ICC(1), this ICC assumes that the variance of the raters is only adding noise to the estimate of the ratees, and that mean rater error = 0. Or in other words, while a particular rater might rate Ratee 1 high and Ratee 2 low, it should all even out across many raters. Like ICC(1), it assumes a random effects model for raters, but it explicitly models this effect – you can sort of think of it like “controlling for rater effects” when producing an estimate of reliability. If you have the same raters for each case, this is generally the model to go with. This will always be larger than ICC(1) and is represented in SPSS as “Two-Way Random” because 1) it models both an effect of rater and of ratee (i.e. two effects) and 2) assumes both are drawn randomly from larger populations (i.e. a random effects model).

If your answer to Question 1 is yes and your answer to Question 2 is “population”, you need ICC(3). In SPSS, this is called “Two-Way Mixed.” This ICC makes the same assumptions as ICC(2), but instead of treating rater effects as random, it treats them as fixed. This means that the raters in your task are the only raters anyone would be interested in. This is uncommon in coding, because theoretically your research assistants are only a few of an unlimited number of people that could make these ratings. This means ICC(3) will also always be larger than ICC(1) and typically larger than ICC(2), and is represented in SPSS as “Two-Way Mixed” because 1) it models both an effect of rater and of ratee (i.e. two effects) and 2) assumes a random effect of ratee but a fixed effect of rater (i.e. a mixed effects model).

After you’ve determined which kind of ICC you need, there is a second decision to be made: are you interested in the reliability of a single rater, or of their mean? If you’re coding for research, you’re probably going to use the mean rating. If you’re coding to determine how accurate a single person would be if they made the ratings on their own, you’re interested in the reliability of a single rater. For example, in our Facebook study, we want to know both. First, we might ask “what is the reliability of our ratings?” Second, we might ask “if one person were to make these judgments from a Facebook profile, how accurate would that person be?” We add “,k” to the ICC rating when looking at means, or “,1” when looking at the reliability of single raters. For example, if you computed an ICC(2) with 8 raters, you’d be computing ICC(2,8). If you computed an ICC(1) with the same 16 raters for every case but were interested in a single rater, you’d still be computing ICC(2,1). For ICC(#,1), a large number of raters will produce a narrower confidence interval around your reliability estimate than a small number of raters, which is why you’d still want a large number of raters, if possible, when estimating ICC(#,1).

After you’ve determined which specificity you need, the third decision is to figure out whether you need a measure of absolute agreement or consistency. If you’ve studied correlation, you’re probably already familiar with this concept: if two variables are perfectly consistent, they don’t necessarily agree. For example, consider Variable 1 with values 1, 2, 3 and Variable 2 with values 7, 8, 9. Even though these scores are very different, the correlation between them is 1 – so they are highly consistent but don’t agree. If using a mean [ICC(#, k)], consistency is typically fine, especially for coding tasks, as mean differences between raters won’t affect subsequent analyses on that data. But if you are interested in determining the reliability for a single individual, you probably want to know how well that score will assess the real value.

Once you know what kind of ICC you want, it’s pretty easy in SPSS. First, create a dataset with columns representing raters (e.g. if you had 8 raters, you’d have 8 columns) and rows representing cases. You’ll need a complete dataset for each variable you are interested in. So if you wanted to assess the reliability for 8 raters on 50 cases across 10 variables being rated, you’d have 10 datasets containing 8 columns and 50 rows (400 cases per dataset, 4000 total points of data).

A special note for those of you using surveys: if you’re interested in the inter-rater reliability of a scale mean, compute ICC on that scale mean – not the individual items. For example, if you have a 10-item unidimensional scale, calculate the scale mean for each of your rater/target combinations first (i.e. one mean score per rater per ratee), and then use that scale mean as the target of your computation of ICC. Don’t worry about the inter-rater reliability of the individual items unless you are doing so as part of a scale development process, i.e. you are assessing scale reliability in a pilot sample in order to cut some items from your final scale, which you will later cross-validate in a second sample.

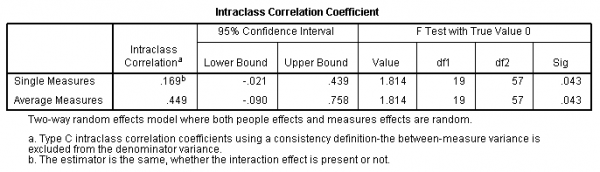

In each dataset, you then need to open the Analyze menu, select Scale, and click on Reliability Analysis. Move all of your rater variables to the right for analysis. Click Statistics and check Intraclass correlation coefficient at the bottom. Specify your model (One-Way Random, Two-Way Random, or Two-Way Mixed) and type (Consistency or Absolute Agreement). Click Continue and OK. You should end up with something like this:

In this example, I computed an ICC(2) with 4 raters across 20 ratees. You can find the ICC(2,1) in the first line – ICC(2,1) = .169. That means ICC(2, k), which in this case is ICC(2, 4) = .449. Therefore, 44.9% of the variance in the mean of these raters is “real”.

So here’s the summary of this whole process:

- Decide which category of ICC you need.

- Determine if you have consistent raters across all ratees (e.g. always 3 raters, and always the same 3 raters). If not, use ICC(1), which is “One-way Random” in SPSS.

- Determine if you have a population of raters. If yes, use ICC(3), which is “Two-Way Mixed” in SPSS.

- If you didn’t use ICC(1) or ICC(3), you need ICC(2), which assumes a sample of raters, and is “Two-Way Random” in SPSS.

- Determine which value you will ultimately use.

- If a single individual, you want ICC(#,1), which is “Single Measure” in SPSS.

- If the mean, you want ICC(#,k), which is “Average Measures” in SPSS.

- Determine which set of values you ultimately want the reliability for.

- If you want to use the subsequent values for other analyses, you probably want to assess consistency.

- If you want to know the reliability of individual scores, you probably want to assess absolute agreement.

- Run the analysis in SPSS.

- Analyze>Scale>Reliability Analysis.

- Select Statistics.

- Check “Intraclass correlation coefficient”.

- Make choices as you decided above.

- Click Continue.

- Click OK.

- Interpret output.

- Shrout, P., & Fleiss, J. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (2), 420-428 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [↩]

| Previous Post: | Learn About Our University Library Through Minecraft |

| Next Post: | New Research Links Social Media Marketing and Purchase Intentions |

Thank Dr. Landers. Very informative. Just what I was looking for in my research on ICC and inter-rater reliability.

Glad to help! This has actually become one of my most popular posts, so I think there really was a need here. Just be sure to note that this terminology is the Shrout and Fleiss terminology – for example, some researchers refer to ICC(1,k) as ICC(2), especially in the aggregation/multilevel models literature.

Dear Dr. Landers,

I am currently doing my dissertation for which I have developed a 25-item test that requires explanation from students; hence, a rubric was used for checking . The test was pilot tested to 105 students. My question is: Is it fine to have just two raters, each rater rating all 25 explanations of the 105 students? Or is it necessary that there are at least 3 raters? What type of ICC is appropriate to use and how do I go about it in SPSS?

Thank you so much and more power!

I don’t at all understand what your raters or doing or why from your description, so that makes it difficult to answer this. The number of raters you need is dependent on what you want to do with the scores next. The appropriate type of ICC is dependent on your answers to the various questions in this article above. The process for calculating it is also described above.

Very informative and helpful, well explained and easy to use – thank you

Dr Landers,

This was very helpful. I just have one question for you. In my research I am averaging my raters to develop a new variable; therefore is it correct that the Average Measures ICC is the coefficient I am most interested in?

Yes, if you’re using the average of the ratings you collected in further analyses, the reliability of that variable will be the “average measures” (,k) version.

Thank you so much. I had looked to other informations and have still some doubts. Your explanations are so clear. You really know how to explain to non-statistic people.

Congratulations for your didactic ability.

Sofía

In my case, I have only two raters (a sample) rating many individuals each (around 50), and rating them according to different criteria (for example: accuracy, speed, etc).

According to your explanations, I should apply 2-way random ANOVA with absolute agreement, since I am interested not only in consistency, but also in the reliability of a single rater.

My doubt is if I am able to apply this ICC, or as I only have two raters, if it would be preferable to apply a Pearson correlation.

Thank you very much.

Best wishes,

Sofía

Hello again,

Actually I am trying to validate a assessment rating scale, which evaluates different criteria by observing a subject.

Two observers rated then 50 subjects with this scale.

In order to validate the scale, I should validate each one of its questions (criterion).

I should do an ICC for each one of my criteria, isn’t it?

I guess if Sig < 0.05 for a criteria and if I obtain a high intraclass correlation (what should be considered high? greater than 0.75?) I can deduce that that particular criterion is consistent and reliable, even if I only had two raters?

Am I right?

Thank you very much.

Sofía

ICC only assesses reliability; this is a distinct concept from validation. For a measure to be valid, it must also be reliable, but reliability alone does not guarantee validity. So computing ICC should be only part of a larger validation strategy.

To assess ICC when looking at a scale, compute the scale mean for each rater separately first. Then compute ICC. If you are using the same 2 raters for every person, and you want to assess the reliability of a single rater, you are correct: you need ICC(2,1), which is 2-way Random with Absolute Agreement.

I would not worry about statistical significance testing in this context. A statistically significant ICC just tells you that it’s unlikely that your ICC was drawn from a population where the true ICC was 0. That’s not a very interesting question for what you’re doing. Instead, just see how high ICC is.

The general recommendation by Cohen was that reliability be above 0.7, which means 70% of observed variance is “real” variance. But it really depends on what you’re willing to accept, or what the research literature suggests is typical/necessary. Any non-perfect reliability will decrease the validity of your measure, so it’s mostly a matter of how large you are willing that effect to be.

Thank you very much for your reply.

Then, I understand that I can do ICC with only two raters (they are the same two raters for every person) to test the reliability of my scale.

However, I do not understand why should I do the mean… do you mean:

a) the mean of the ratings of all questions for each person and for each rater

b) the mean of the ratings of a single question given by one rater to all the people

I guess you meaned option a), because otherwise, for option b), if my scale has 13 questions to rate, I should first of all calculate the mean of the answers of rater1 for all those 13 questions, then the mean of rater2. If I do this I would have 13 values for each of the raters, and then, doing the ICC with just two measures (the mean of each rater) I guess it does not make sense?

However, even if you mean option a), wouldn’t that give a reliability of the whole test (composed by 13 questions) but not of every single question?

Can´t I do:

1) the ICC for each question calculating the ICC comparing all the ratings given by each rater to all the people for that particular question.

2) the mean, according to option a) to calculate the ICC of the whole scale.

Thank you very much for your time and for your fast response.

Best wishes

Sorry – I should been clearer. By “scale,” I assumed you meant you have multiple items (questions) assessing the same construct.

You should assess reliability for each distinct measurement concept. So if you had 13 questions that all assessed “happiness,” you should compute ICC on the mean of those items. If you have 13 questions that all assess different things, you should compute 13 ICCs. But I will warn you that ICC tends to be low if you are assessing any psychological constructs with only single items each.

Thank you very much for your reply. Now it is clear.

On the other hand, do you know about any site where I can find a more detailed explanation about how to validate a scale? (not only reliability, but also validity).

Best wishes,

Sofia

Thank you Dr. Landers, this way very helpful!

May I have one question, just to make it clear for myself.

If I have a 15-item interview (with a scale 1-2-3) and 10 raters (population, and always the same 10 raters) rate 5 patients. I am interested in the average reliability of the raters and also I would like to know the reaters’ individual “performance”. This would be a “Two way mixed” in SPSS.

Should I then create a database for each item of the interview (that’d be 15 databases) and run “Two way mixed” and “Absolute agreement”, right? And then computing the mean of the results? Or can I do that I create a database for each patient with 15 rows (items) and 10 columns (raters) and run the Two way mixed?

I guess I am a little bit confused what does “add ,k to the ICC” or “add ,1” mean?

THank you very much for your help!

Best regards

Mark

@Sofia – Validation is a much, much more complicated concept than reliability. I don’t know of any websites that explain it very clearly, although there are entire textbooks devoted to it.

@Mark – Are the 15 questions assessing the same thing? If so, compute a scale mean and then run your statistics on that. You would only look at reliability by item if you were going to use those 15 items individually later. If that’s what you’re going to do, yes, you would need separate SAV files for each database.

,k means you are referring to an ICC of the average ratings. ,1 means you are referring to an ICC of an individual rater. You cannot use ICC to identify the “performance” of any particular rater; instead, all you can tell is the reliability of raters on average or the reliability of a single rater taken at random from your population.

Thank you very much, Richards. Your comments have been of great help. Do you know if there is any statistical forum where to ask doubts online?

Best wishes,

Sofía

Validation isn’t so much statistics as it is a family of research methods. But sure – one statistics forum you might find useful is http://stats.stackexchange.com/

Dear Dr. Landers,

thank you for your answer!

THe 15 item measure the same psychological construct (borderline disorder), but not the same thing, since the items about different symptomps of the disorder – I think this is what you asked. So, later in the research these items will be used (asked) separately and will be evaluated by the raters based on the interview.

So, if I get it right, in this case I’ll need separate SAV files for each item and then compute a mean and that’ll be the overall ICC of the raters.

I can I use ICC for binary data (e.g. 1=borderline, 2=not borderline)? Because we would like to not just compute ICC for the individual items and the overall interview, but we’d like to compute ICC for the final diagnosis (borderline/not borderline).

…and thank you, now I understand what ‘single measure’ means!

Regards, and thank you very much for your kind answers!

Mark Berdi

@Mark – if you are interested in assessing the reliability of symptom ratings, then you need ICCs for each item. If you are interested in assessing inter-rater reliability in general (i.e. the reliability relevant to any future statistics computed using a “borderline score”), you’ll want to compute the scale means for each rater and compute ICC for those means. You should not take an average of ICCs, as that’s not an interpretable value – if you’re interested in the ICC of overall scales, that’s what you should compute the ICC on.

For binary data, you could use ICC, but it is not recommended – I would look into Fleiss’ kappa.

Thank you!

I understood it. I just computed what I needed.

Best regards

Mark Berdi

Hello Dr. Landers,

First, thank you for an excellent resource. We are following your method to conduct interrater reliability. In reference to question 2: sample v. population of raters, what criteria do you use to determine the response?

Additionally, we have found an error will result when raters are in perfect agreement (e.g., all 3 raters assign a score of 2 for a given item). Is this due to the lack of variance and inability to proceed with additional calculations?

Any advice or direction is welcomed.

Sincerely,

Emily and Laura

@Emily & Laura – It just depends on what you want to generalize to. If your raters are the only raters that you ever want to worry about, you have a population. If they are a random sample of such raters, you have a sample. For example, if you have three people watch videos and make ratings from them, the three people you have watching the videos are only three possible raters – you could just as easily have chosen another three drawn from the same population. Therefore, they are a sample of raters.

As for your second question, if your raters are always in perfect agreement, you have no need for ICC. Your reliability is 100% (1.0), so there is nothing to assess.

Thank you for this helpful website. I just want to be clear about question 1. If I have 100 fifteen second clips of children misbehaving and I have a single rater (Sally) rate from 1-7 how bad the misbehavior is for each clip and I have Sam give the same misbehavior ratings to 33 of those clips, it sounds like I have answered “yes” to question 1. Is that right?

And if there is any deviation from this (e.g. I have Bill rate another 33 clips that Sally rated), I answer “no”. Is that also correct?

@Camilo – I’m not sure that I’m clear on your premise, but I will take a stab at it.

If Sally and Sam rate identical clips, then yes – you have “yes” to Q1. However, if you have 2 ratings for 33 clips and only 1 rating for 66 clips, you can only calculate ICC for those 33 clips. If you want to generalize to all the clips (e.g. if you were using all 100 clips in later analyses), you’d need to use the “Single Measure” version of ICC, since you only have 1 rater consistently across all ratees.

If you had Bill rate an additional 33 clips, you’d still have 2 ratings for 66 clips and 1 rating for 33 clips, so nothing has changed, procedurally. However, because you have a larger sample, you’d expect your ICC to be more accurate (smaller confidence interval).

The only way to use the “Average Measures” version of ICC is to have both raters rate all clips (two sets of 100 ratings).

Hi Dr Landers,

This is by far the most helpful post I have read.

I still have a question or two though..

I am looking at the ICC for 4 raters (sample) who have all rated 40 cases.

I therefore think I need the random mixed effects model (ICC, 2,k)

In SPSS i get a qualue for single measures and average measures and I am not sure which i want. My assumption is average measures?

Also i have seen variations in how ICC values are reported and I wondered if you knew the standard APA format, my guess would be [ICC(2, k) = ****].

Any guidance would be very much appreciated.

Many thanks, Anne-Marie.

@Anne-Marie – the “k” indicates that you want Average Measures. Single Measure would be ,1. If you’re using their mean rating in later analyses, you definitely want ,k/Average Measures.

As for reporting, there is no standard way because there are several different sources of information on ICC, and different sources label the different types slightly differently (e.g. in the multilevel modeling literature, ICC(2,1) and ICC(2,k) are sometimes referred to as ICC(1) and ICC(2), respectively, which can be very confusing!).

If you’re using the framework I discuss above, I’d recommend citing the Shrout & Fleiss article, and then reporting it as: ICC(2,4) = ##.

Dr Landers,

Thank you so much!

All calculated and all looking good!

Anne-Marie.

Very useful and easy to understand. I am currently completing my dissertation for my undergraduate physiotherapy degree and stats is all very new. This explained it really easily. Thanks again!

I am training a group of 10 coders, and want to assess whether they are reliable using training data. During training, all 10 code each case, but for the final project, 2 coders will code each case and I will use the average of their scores. So for the final project, I will calculate ICC (1, 2), correct? Then what should I do during training–calculating ICC (1, 10) on the training cases will give me an inflated reliability score, since for the real project it will be only 2 coders, not 10?

@Catherine – It’s important to remember that reliability is situation-specific. So if you’re not using the training codes for any later purpose, you don’t really need to compute their reliability. You would indeed just use ICC(1,2) for your final reliability estimate on your final data. However, if you wanted to get your “best guess” now as to what reliability will be for your final coding, using your training sample to estimate it, you could compute ICC(1,1) on your training sample, then using the Spearman-Brown prophesy formula to identify what the reliability is likely to be with 2 raters. But once you have the actual data in hand, that estimate is useless.

Hello,

I have a small question that builds on the scenario described by Emily & Laura (posted question and answer on March 26, 2012 in regards to the error that results when raters are in perfect agreement).

In my case, only a portion of my 21 raters are in perfect agreement, and so SPSS excludes them from the reliability analyses, resulting in (what I would think to be) an artificially low ICC value, given that only ‘non-agreeing’ raters are being included. Is there a way to deal with this?

Many thanks,

Stephanie

@Stephanie – My immediate reaction would be that ICC may not be appropriate given your data. It depends a bit on how many cases you are looking at, and what your data actually looks at. My first guess is that your data is not really quantitative (interval or ratio level measurement). If it isn’t, you should using some variant of kappa instead of ICC. If it is, but you still have ridiculously high but not perfect agreement, you might simply report percentage agreement.

Dear Dr. Landers,

You are indeed correct – my data are ordered categorical ratings. 21 raters (psychiatrists) scored a violence risk assessment scheme (comprised of 20 risk factors that may be scored as absent, partially present, or present – so a 1,2,3 scale) for 3 hypothetical patients. So I am trying to calculate the reliability across raters for each of the 3 cases.

My inclination was to use weighted kappa but I was under the impression it was only applicable for designs with 2 raters?

Thanks again,

Stephanie

Ahh, yes – that’s the problem then. ICC is not really designed for situations where absolute agreement is common – if you have interval level measurement, the chance that all raters would score exactly “4.1” (for example) is quite low.

That restriction is true for Cohen’s kappa and its closest variants – I recommend you look into Fleiss’ kappa, which can handle more than 2 raters, and does not assume consistency of raters between ratings (i.e. you don’t need the same 3 raters every time).

Thank you

Can you explain to me the importance of upper and lower Bound (CI 95%)?. “How to take advantage of” CI?

That’s not really a question related to ICC. If you are looking for general help on confidence intervals, this page might help: http://stattrek.com/estimation/confidence-interval.aspx

Thank you for this clear explanation of ICCs. I was wondering if you might know about them in relation to estimate intrarater reliability as well? It seems as if the kappa may provide a biased estimate for ordinal data and the ICC may be a better choice. Specifically, I’m interested in the intrarater reliability of 4 raters’ rating of an ordinal 4 point clinical scale that evaluates kidney disease, each rater rated each patient 2 times.

I’m using SAS and can’t seem to get the ICC macro I used for interrater reliabilty to work. I’m wondering if the data need to be structured with rater as variables (as you say above)? If so, do you know if I would include the two measurements for each patient in a single observation or if I should make two observations per patient?

Thank you-

Lisa

I don’t use SAS (only R and SPSS), so I’m afraid I don’t know how you’d do it there. But I don’t think I’d do what you’re suggesting in general unless I had reason to believe that patients would not change at all over time. If there is true temporal variance (i.e. if scores change over time), reliability computed with a temporal dimension won’t be meaningful. ICC is designed to assess inter-rater consistency in assessing ratees controlling for intra-rater effects. If you wanted to know the opposite (intra-rater consistency in assessing ratees controlling for inter-rater effects), I suppose you could just flip the matrix? I am honestly not sure, as I’ve never needed to do that before.

Thanks for yuor thoughts.

Hello Richard,

Thanks a lot for your post. I have one question: I built an on-line survey that was answered by 200 participants. I want to know if the participants did not show much variance in their answers so to know that the ratings are reliable. For that matter, I am running a One-way random effects model and then I am looking at the average measures.

That’s the way I put it:

Inter-rater reliability (one-way random effects model of ICC) was computed using SPSS (v.17.0). One-way random effects model was used instead of Two-way random effects model because the judges are conceived as being a random selection of possible judges, who rate all targets of interest. The average measures means of the ICC was 0.925 (p= 0.000) which indicates a high inter-rater reliability therefore reassuring the validity of these results (low variance in the answers within the 200 participants).

I would be happy if you could tell me whether a one-way random effects model of ICC and then looking at the average measures is the way to go.

Thank you,

John

@John – Your study is confusing to me. Did you have all 200 participants rate the same subject, and now you are trying to determine the reliability of the mean of those 200 participants? If so, then you have done the correct procedure, although you incorrectly label it “validity.” However, I suspect that is not what you actually wanted to do, since this implies that your sample is n = 1. If you are trying to assess variance of a single variable across 200 cases, you should just calculate the variance and report that number. You could also compute margin of error, if you want to give a sense of the precision of your estimate. If you just want to show “variance is low,” there is no inferential test to do that, at least in classical test theory.

Thank you for your answer, Richard.

I built an on-line survey with a 100 items.

Subjects used a 5 point Lickert scale to indicate how easy was to draw those items.

200 subjects answered the on-line survey.

I want to prove the validity of the results. If the ICC cannot be used for that matter. Can I use the Cronbach’s alpha?

Thanks for your time.

Best,

John

@John – Well, “reliability” and “validity” are very different concepts. Reliability is a mathematical concept related to consistency of measurement. Validity is a theoretical concept related to how well your survey items represent what you intend them to represent.

If you are trying to produce reliability evidence, and you want to indicate that all 100 of your items measure the same construct, then you can compute Cronbach’s alpha on those items. If you have subsets of your scale that measure the same construct (at least 2 items each), you can compute Cronbach’s alpha for each. If you just asked 100 different questions to assess 100 different concepts, alpha isn’t appropriate.

If your 100 items are all rating targets theoretically randomly sampled from all possible rating targets, and you had all 100 subjects rate each one, you could calculate ICC(2). But the measure count depends on what you wanted to do with those numbers. If you wanted to compute the mean for each of the 100 rating subjects and use that in other analyses, you’d want ICC(2, 200). If you just wanted to conclude “if one person rates one of these, how reliable will that person’s ratings be?”, then you want ICC(2, 1).

Thank you for your answer, Richard.

I will use Chronbach’s alpha for internal consistency. That way I can say that my survey measured the same general construct: the imageability of the words.

I will use ICC (2,1)(two-way random, average measures) for inter-rater reliability. That way I can say if the subjects answered similarly.

#I am interested in the mean of each item to enter the data in a regression analysis (stepwise method). I am interested then in saying that a word like ‘apple’ has a mean imageability of 2 out of 5. I am not interested in the mean of the answers of each subject. That is, subject 1 answered 3 out of 5 all the the time.

#After running those two statistics, is it OK to talk about validity?

Thanks again.

Best,

John

You can certainly *talk* about validity as much as you want. But the evidence that you are presenting here doesn’t really speak to validity. Statistically, the only thing you can use for this purpose is convergent or discriminant validity evidence, which you don’t seem to have. There are also many conceptual aspects of validity that can’t be readily measured. For example, if you were interested in the “imageability” of the words, I could argue that you aren’t really capturing anything about the words, but rather about the people you happened to survey. I could argue that the 200 pictures you chose are not representative of all possible pictures, so you have biased your findings toward aspects of those 200 pictures (and not a general property of all pictures). I could argue that there are cultural and language differences that change how people interpret pictures, so imageability is not a meaningful concept anyway, unless it is part of a model that controls for culture. I could argue that color is really the defining component, and because you didn’t measure perceptions of color, your imageability measure is meaningless. I suggest reading Shadish, Cook, and Campbell (2002) for a review of validation.

But one key is to remember: a measure can be reliable and valid, reliable and invalid, or unreliable and invalid. Reliability does not ensure validity; it is only a necessary prerequisite.

Thank you for the note on validity,Richard.

Please let me know if the use I give to the Chronbach’s alpha for internal consistency and the ICC (2,1)(two-way random, average measures) for inter-rater reliability is reasonable. Those are eery statistics for me, hence, it is important for me to know your take on it.

About the imageability ratings. We gave 100 words to 200 subjects. The subjects told us in a 5 point scale how did they think the words can be put on a picture.

Thanks again.

Best,

John

ICC(2,1) is two-way random, single measure. ICC(2,100) would be your two-way random, average measures. Everything you list is potentially a reasonable thing to do, but it really depends on what you want to ultimately do with resulting values, in the context of your overall research design and specific research questions. I would at this point recommend you bring a local methods specialist onto your project – they will be able to help you much more than I can from afar.

Thank you for your answer, John.

I will try to ask a local methods specialist. So far, the people around me are pretty rusty when it comes to helping me out with all this business.

Thanks again.

Best,

John

Hello Richard,

Thank you for the wonderfull post, it helped very much!

I have a question aswell, if you can still answer, since it’s been a while since anyone posted here.

I have a survey with 28 items, rated 1 -7, by 6 people. I need to know how much agreement is between the 6 on this rating and if possible the items that reach the highest rating (that persons agree most on). It’s a survey with values (single worded items) and I have to do an aggregate from these 6 people’s rating, if they agree on the items, so I can later compare it with the ratings of a larger dataset of 100 people. Let us say that the 6 raters must be have high reliability because they are the ones to optimaly represent the construct for this sample of 105 (people including the raters).

Basicaly: 1.I need to do an aggregate of 6 people’s ratings (that’s why I need to calculate the ICC), compare the aggregate of the rest of the sample with this “prototype”, see if they correlate.

2. Determine the items with largest agreement.

What I don’t understand is if I use the items as cases and run an ICC analysis, two way mixed and than look at the single or average?

Hope this isn’t very confusing and you can help me with some advice.

Thank you,

Andra

@Andra – It really depends on which analysis you’re doing afterward. It sounds like you’re comparing a population of 6 to a sample of 99. If you’re comparing means of those two groups (i.e. you using the means in subsequent analyses), you need the reliability of the average rating.

Dear Richard,

Thank you for your answer. I think though that I’ve omitted something that isn’t quite clear to me: the data set in spss will be transposed, meaning I will have my raters on columns and my variables on rows? Also in the post you say to make a dataset for every variable but in this case my variables are my “cases” so I assume I will have only a database with 9 people and 28 variables on rows and compute the ICC from this?

I have yet another question, hope you can help me. What I have to do here is to make a profile similarity index as a measure of fit between some firm’s values as rated by the 9 people and the personal values of the rest of the people, measured on the same variables. From what I understand this can be done through score differences or correlations between profiles. Does this mean that I will have to substract the answers of every individual from the average firm score or that I’ll have to correlate each participant’s scores with that of the firm and then have a new variable that would be a measure of the correlation beween the profiles? Is there any formula that I can use to do this; I have the formula for difference scores and correlation but unfortunatelly my quite moderate mathematical formation doesn’t help ..

I sincerelly hope that this isn’t far beyond the scope of your post and you can provide your expertize for this!

Appreciatively,

Andra

@Andra – It does not sound like you have raters at all. ICC is used in situations like this: 6 people create scores for 10 targets across 6 variables. You then compute 6 ICCs to assess how well the 6 people created scores for each of the 10 targets. It sounds like you may just want a standard deviation (i.e. spread of scores on a single variable), which has nothing to do with reliability. But it is difficult to tell from your post alone.

For the rest of your question, it sounds like you need a more complete statistical consult than I can really provide here. It depends on the specific index you want, the purpose you want to apply it toward, further uses of those numbers, etc. There are many statisticians with reasonable consulting rates; good luck!

Okay Richard, I understand, then I can’t use the ICC in this case. Thought I could because at least one author in a similar paper used it … something like this (same questionnaire, different scoring, theirs had q sort mine is lickert):

“As such, the firm informant’s Q Sorts were averaged, item by

item, for each [] dimension representing each firm.Using James’ (1982) formula, intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for ascertaining the

member consensus on each dimension. ICC was calculated by using the following formula[]”

Maybe the rWG would be better?

Anyhow, thank you very much for trying to answer, I will re-search the online better for some answers 🙂

All the best,

Andra

Hi Richard,

I just wanted to check something.

If i have 28 cases, and 2 raters rating each case, from a wider population of raters, I think I need…

Two-way Random effects model

ICC 2, 2. for absolute agreement.

When I get the output, do I then report the average measures ICC value, rather than the single measures, as I want to identify the difference between raters?

Many thanks, Anne-Marie.

@Anne-Marie – Reliability doesn’t exactly assess “the difference between raters.” You are instead capturing the proportion of “true” variance in observed score variance. If you intend to use your mean in some later analysis, you are correct. If you are just trying to figure out how consistently raters make their ratings, you probably want ICC(2,1).

Hi Richard, I want to calculate ICC(1) and ICC(2) for the purpose of aggregating individual scores into group level scores. Would the process be similar to what you described for inter-rater reliability.

I would imagine that in the case the group would be equivalent to the rater. That is, instead of looking within rater versus between rater variance, I want within group versus between group variance? Therefore would I just put the grouping IDs along the columns (rather than rater) and the score for each group member along the row?

However, I have varying group sizes, so some groups have 2 member and some have as many as 20. It seems like that could get quite messy… Maybe there is some other procedure that is more appropriate for this?

Dear Richard

thank you, this makes things much clearer concerning how to choose the appropriate ICC.

Can I ask if you have any paper examples on how to report ICCs?

Thank you for your time

Best wishes

Laura

Dear Dr. Landers,

Thank you very much for the information on this forum!

Unfortunately, after studying all the responses on this forum I still have a question:

In total I have 292 cases from which 13 items were rated on a 4-point rating scale. Coder 1 has rated 144 cased, Coder 2 has rated 138 cases and 10 cases were treated as training cases. Three items were combined in a composite score and this score will be used in future studies. So in future studies I want to report this composite score on all 292 cases.

The question now is of course: “What is the intercoder reliability between Coder 1 and Coder 2 on the composite score?” To assess reliability between the coders I want to compare the composite score of both Coders on 35 cases (these were scored by both Coder 1 and Coder 2).

I think I have to use the ICC (2) and measure absolute agreement. Is this correct?

My doubt is if I have to look at the ‘single measure’ or ‘average measure’ in SPSS?

I hope you can help me. Many thanks in advance.

Janneke

@Gabriel – You can use ICC as part of the procedure to assess if aggregation is a good idea, but you can’t do this if group sizes vary substantially. I believe in this case, you want to use within-groups r, but I’m not sure – I don’t do much research of this type.

@Laura – Any paper that reports an ICC in your field/target journal would provide a great example. This varies a bit by field though – even ANOVA is presented different across fields.

@Janneke – You should use “absolute agreement” and “single measure.” Single measure because you’re using ratings made by only one person in future analyses. If you had both raters rate all of them, and then used the mean, you would use “average measure.”

Dear Dr. Landers,

Thank you very much for your quick and clear answer.

Best regards, Janneke

Dear Dr. Landers,

Thank you for such wonderful article. I am sure it is very beneficial to many people out there who are struggling.

I am trying to study the test-retest reliability of my questionnaire (HIV/AIDS KAP survey).

The exact same set of respondents completed the same questionnaire after a 3-week interval. Though anonymous, for the same respondent, I can link both tests at time1 and time2.

Through a lot a of researching, literatures suggest Kappa coefficients for categorical variables and ICC for continuous variables (please comment if I get that wrong).

However, I am still uncertain regarding the model of ICC in SPSS that I should use for my study.

The bottom line conclusion that I would like to make is that the questionnaire is reliable with acceptable ICC and Kappa coefficients.

I would really appreciate your suggestion.

Thank you very very much.

Teeranee

@Teeranee – Neither ICC nor Kappa are necessarily appropriate to assess test-retest reliability. These are both more typically estimates of inter-rater reliability. If you don’t have raters and ratees, you don’t need either. If you have a multi-item questionnaire, and you don’t expect scores to vary at the construct level between time points, I would suggest the coefficient of equivalence and stability (CES). If you’re only interested in test re-test reliability (e.g. if you are using a single-item measure), I’d suggest just using a Pearson’s correlation. And if you are having two and only two raters make all ratings of targets, you would probably use ICC(2).

Dr. Landers,

Thank you very much for your reply.

I will look into CES as you have suggested.

Thank you.

Dear Dr. Landers,

Many thanks for your summary, it very, very helpful. I wanted to ask you one more question, trying to apply the information to my own research. I have 100 tapes that need to be rated by 5 or 10 raters and I am trying to set pairs of raters such that each rater codes as few tapes as possible but I am still able to calculate ICC. The purpose of this is to calculate inter-rater reliability for a newly developed scale.

Thank you very much.

@Violeta – I’m not sure what your question is. Reliability is a property of the measure-by-rater interaction, not the measure. For example, reliability of a personality scale is defined by both the item content and the particular sample you choose to assess it (while there is a “population” reliability for a particular scale given a particular assessee population, there’s no way to assess that with a single study or even a handful of studies). Scales themselves don’t have reliability (i.e. “What is the reliability of this scale?” is an invalid question; instead, you want to know “What was the reliability of this scale as it was used in this study?”). But if I were in your situation (insofar as I understand it), I would probably assign all 10 raters to do a handful of tapes (maybe 20), then calculate ICC(1,k) given that group, then use the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula to determine the minimum number of raters you want for acceptable reliability of your rater means. Then rate the remainder with that number of raters (randomly selected for each tape from the larger group). Of course, if they were making ratings on several dimensions, this would be much more complicated.

Dear Dr. Landers,

Thank you very much for your clarifications and for extracting the question from my confused message. Thank you very much for the solution you mentioned, it makes a lot of sense, and the main impediment to applying it in my project is practical – raters cannot rate more than 20 tapes each for financial and time reasons. I was thinking of the following 2 scenarios: 1) create 10 pairs of raters, by randomly pairing the 10 raters such that each rater is paired with 2 others; divide the tapes in blocks of 10 and have each pair of raters code a block of 10 tapes; in the end I would calculate ICC for each of the 10 pairs of raters, using ICC(1) (e.g., ICC for raters 1 and 2 based on 10 tapes; ICC for raters 1 and 7 based on 10 tapes, etc.); OR, 2) create 5 pairs of raters, by randomly pairing the 5 raters such that is rater is paired with one other rater; divide the tapes in blocks of 20 and have each pair of raters code a block of 20 tapes; I would end up with 5 ICC(1) (e.g., ICC for raters 1 and 5 based on 20 tapes, etc.). Please let me know if these procedures make sense and if yes, which one is preferrable. Thank you very much for your time and patience with this, it is my first time using this procedure and I am struggling a bit with it. I am very grateful for your help.

You need ICC(1) no matter what with different raters across tapes. It sounds like you only want 2 raters no matter what reliability they will produce, in which case you will be eventually computing ICC(1,2), assuming you want to use the mean rating (from the two raters) in subsequent analyses. If you want to assess how well someone else would be able to use this scale, you want ICC(1,1).

As for your specific approaches, I would not recommend keeping consistent pairs of raters. If you have any rater-specific variance contaminating your ratings, that approach will maximize the negative effect. Instead, I’d use a random pair of raters for each tape. But I may not be understanding your approaches.

Also, note that you’ll only have a single ICC for each type of rating; you don’t compute ICC by rater. So if you are having each rater make 1 rating on each tape, you’ll only have 1 ICC for the entire dataset. If you are having each rater make 3 ratings, you’ll have 3 ICCs (one for each item rated). If you are having each rater make 3 ratings on each tape but then take the mean of those 3 ratings, you’ll still have 1 ICC (reliability of the scale mean).

Thank you very much, this is so helpful! I think that it is extraordinary that you take some of your time to help answering questions from people that you don’t know. Thank you for your generosity, I am very grateful!

Dear Richard,

I have two questions:

– Can you use the ICC if just one case (person) is rated by 8 raters on several factors (personality dimensions)? So not multiple cases but just one.

– Can you use ICC when the original items (which lead to a mean per dimension) are ordinal (rated on a 1-5 scale)? So can I treat the means of ordinal items as continues or do I need another measure of interrater reliability?

I hope you can help me!

1) No; ICC (like all reliability estimates) tells you what proportion of the observed variance is “true” variance. ICC’s specific purpose is to “partial out” rater-contributed variance and ratee-contributed variance to determine the variance of the scale (given this measurement context). If you only have 1 case, there is no variance to explain.

2) ICC is for interval or higher level measurement only. However, in many fields in the social sciences, Likert-type scales are considered “good enough” to be treated as interval. So the answer to your question is “maybe” – I’d recommend consulting your research literature to see if this is common.

Dr. Landers,

In your response to Gabriel on 8/15/12, you indicated that ICC(1) is appropriate for ratings made by people arranged in teams when the teams vary in size (i.e., number of members). However, a reviewer is asking for ICC (2) for my project where my teams also vary in size. How would you respond?

Many kind thanks!

Looking back at that post, I actually don’t see where I recommended that – I was talking about ICC in general. As I mentioned then, the idea of aggregation in the teams literature is more complex than aggregation as used for coding. For an answer to your question, I’d suggest taking a look at:

Bliese, P. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability. In K. Klein and S. Kozlowski (Eds), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (pp. 349-381).

Hofmann, D. A. (2002). Issues in multilevel research: Theory development, measurement; and analysis. In S. Rogelberg (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Klein, K. l, Dansereau, F., and Hall, Rl (1994). Levels issues in theory development, data collection, and analysis. Academy of Management Review, 19, 195-229.

Thank you! Bliese (2000) was particularly helpful.

Dr. Landers,

Regarding consistency across raters – I have an instrument with more items (30) and 100 persons rating the items. If I analyse the internal consistency of the scale in SPSS and choose the ICC two way random option, can I use the result for the ICC as indicating level of consistency on scale items across my 100 raters? Is that correct or are there other calculations I must perform? I need to know if the ratings of the items are consistent to form an aggregate.

Thank you, hopefully you can provide some advice!

I don’t think you’re using the word “rating” in the methodological sense that it is typically used related to ICC. By saying you have 100 persons rating the items, you imply that those are not the “subjects” of your analysis. Based on what you’re saying, you have 100 _subjects_, which are each assessed with 30 items (i.e. 3000 data points). If so, you probably want coefficient alpha (assuming your scale is interval or ratio level measurement).

Dr Landers,

Thank you for the answer. Perhaps I did not express the issue properly. The 30 items refer to an “individual” (in a way put, or a larger entity, an organization) so the respondents would be assessing someone else on the 30 items, not self-rating themselves.Could I use the ICC as mentioned, by choosing the option from reliability analysis in SPSS in this case, or similarly, more calculations need to be performed?

Anxiously waiting for a response …

It depends. How many people are being assessed by the raters, and a related question, how many total data points do you have? Are the 100 raters scoring the 30 items for 2 others, 3 others, etc?

For example, it’s a very different problem if you have 100 raters making ratings on 50 subjects, each making 2 sets of ratings on 30 items (a total of 3000 data), versus 100 raters making ratings on 100 subjects, each making 1 rating on 30 items (also a total of 3000 data).

If you have 100 raters making ratings on 100 subjects (1 set of 30 ratings each), you have perfectly confounded raters and subjects, and there is no way to determine the variance contributed by raters (i.e. ICC is not applicable). If you have more than 1 rating for each subject, yes – you can calculate ICC for each of your 30 items, or if it’s a single scale, you can calculate scale scores and compute a single ICC on that. If you want to treat the items on the scale as your raters, that’s also a valid reliability statistic, but it still doesn’t assess any inter-rater component.

Hi Dr. Landers..

I came across this useful information as I was searching about ICC.

Thank you for this information explained in a clear way.

I have a question, though.

If, I have 5 raters marking 20 sets of essays. First, each raters will mark the same 20 essays using analytic rubric. Then, after an interval of 2 weeks, they will be given the same 20 essays to be marked with different rubric, holistic rubric. The cycle will then repeated after 2 weeks (after the essays collected from Phase 2), with the same 20 essays & analytic rubric. Finally after another 2 weeks, the same 20 essays and holistic rubric. Meaning, for each type of rubric, the process of rating/marking the essays will be repeated twice for interval of 1 month.

Now, if I am going to look for inter rater reliability among these 5 raters and there are 2 different rubrics used, which category of ICC should I use? Do I need to calculate it differently for each rubric?

If I am looking for inter rater reliability, I don’t need to do the test-retest method & I can just ask the raters to mark the essays once for each type of rubric, and use ICC, am I right?

And can you help me on how I should compute intra rater reliability?

Thank you in advance for you response.

Regards,

Eme

It depends on how you are collecting ratings and what you’re going to do with them. I’m going to assume you’re planning on using the means on these rubrics at each of these stages for further analysis. In that case, for example:

1) If each rater is rating 4 essays (i.e. each essay is rated once), you cannot compute ICC.

2) If each rater is rating 8 essays (i.e. each essay is rated twice), you would compute ICC(1,2).

3) If each rater is rating 12 essays (i.e. each essay is rated thrice), you would compute ICC(1,3).

4) If each rater is rating 16 essays (i.e. each essay is rated four times), you would compute ICC(1,4).

5) If each rater is rating 20 essays (i.e. each essay is rated by all 5 raters) you would compute ICC(2,5)

You’ll need a separate ICC for each time point and for each scale (rubric, in your case).

Intra-rater reliability can be assessed many ways, depending on what your data look like. If your rubric has multiple dimensions that are aggregated into a single scale score, you might use coefficient alpha. If each rubric produces a single score (for example, a value from 0 to 100), I’d suggest test re-test on a subset of essays identical (or meaningfully parallel) to these. Given what you’ve described, that would probably require more data collection.

‘Thank you, Dr Landers, I think it makes sense now. Basically the 30 items make a scale. My 100 raters rate one individual (the organization in which they work, which is the same for all of them) on these 30 items or the scale. So 100 people rate, each of them, every item in the scale once for a rated “entity”. Then, at least if I have understood it correctly, I can report the ICC for the scale and use it as argument for aggregation. Hope I make more sense now .. Please correct me if it is still not a proper interpretation.

It sounds like you have one person making one rating on one organization. You then have 100 cases each reflecting this arrangement. This still sounds like a situation better suited to coefficient alpha, since you are really assessing the internal consistency of the scale, although ICC(2,k) should give you a similar value. You cannot assess the reliability of the raters (i.e. inter-rater reliability0 in this situation – it is literally impossible, since you don’t have repeated measurement between raters.

If by aggregation, you mean “can I meaningfully compute a scale mean among these 30 items?”, note that a high reliability coefficient in this context does not alone justify such aggregation. In fact, because you have 30 items, the risk of falsely concluding the presence of a single factor based upon a high reliability coefficient is especially high. See http://psychweb.psy.umt.edu/denis/datadecision/front/cortina_alpha.pdf for discussion of this concept.

Dr. Landers,

I am trying to determine reliability of portfolio evaluation with 2 raters examining the same portfolios with an approximate 40-item Likert (1-4) portfolio evaluation instrument.

Question 1: If I am looking for a power of .95, how can I compute the minimum number of portfolios that must be evaluated? What other information do I need?

Question 2: After perusing your blog, I think I need to use ICC (3) (Two-way mixed) because the same 2 raters will rate all of the portfolios. I think I am interested in the mean rating, and I think I need a measure of consistency. Am I on the right track?

I appreciate your time and willingness to help all of us who are lost in Statistics-World.

Cindy

For Q1, I assume you mean you want a power of .95 for a particular statistical test you plan to run on the mean of your two raters. This can vary a lot depending on the test you want to run and what your other variable(s) looks like. I suggest downloading G*Power and exploring what it asks for: http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/aap/projects/gpower/

For Q2, are your two raters the only two people that could ever conceivably rate these portfolios? If so, you are correct – ICC(3,2), consistency. If not (for example, if other people trained equally well as these two could do the same job), you probably want ICC(2,2), consistency. ICC(3) is very uncommon, so unless you have a compelling reason to define your two raters as a complete population of raters, I’d stick with ICC(2).

Hi,

This post was very helpful – thank you for putting the information together.

Any thoughts on sample size? If I would like to estimate interrater reliability for various items on a measure, any thoughts on how many cases I should have for each item?

For instance, if I want to know if social workers can provide a reliable measure of impulsitivity (one-item Q on an assessment form with 3 ordinal response options) when first meeting a child, how many reports of impulsivity (N= how many children?) would I need for this to be an accurate determination of interrater reliability?

And is there a suggested sample size of social workers?

Thank you –

I think your conceptualization of reliability may not be quite right. Reliability is itself a function of the raters and the situation they are in – in other words, you don’t check “if” social workers can provide a reliable measure, but instead you have them make ratings and check to see how reliable _they were_. So sample size/power isn’t really an issue – if you have fewer ratings, they will be less reliable. If you have more ratings, they will be more reliable. A reliability question would be, “how many social workers do I need to reliably measure impulsivity given this set of children?” But if you’re interested in determining the reliability of a single social worker as accurately as possible (i.e. minimizing the width of the confidence interval around ICC) to determine how accurate a social worker drawn from your population of social workers might be when making a judgment on their own, that is a different question entirely.

Thank you for getting back to me so quickly.

Yes, you’re right. I wasn’t conceptualizing this accurately. And you’re also right in speculating that I want to know how reliable a single social worker would be when asked to make a judgement on their own, using the provided scale.

After looking more closely at previous posts, it seems I have a situation similar to Stephanie that will require me to use Fleiss’ kappa?

It depends on what your scale looks like. If they are making ratings on an interval- or ratio-level scale, you can (and should) still use ICC. Kappa is for categorical ratings. You would also need to use the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula to convert your kappa to reflect the reliability of a single rater, whereas with ICC, you can just look at ICC(#, 1).

Dr. Landers,

Although there have already been asked so many questions, I still have one. Hopefully you can help me out (because I am totally lost).

I have done a prétest with 36 advertisements. Every advertisement can be categorized in one of the 6 categories. 15 People have watched all the 36 advertisements and placed each advertisement individually in one of the six categories (So for example: Ad1 – Cat. A; Ad2 – Cat D; Ad1 – Cat B, etc). They also have rated how much they liked the advertisement (from 1 – 5).

In my final survey I want to use one or two advertisements per category. But to find out which advertisement belongs in what category I have done the pretest (so which advertisement is best identified as the advertisement that belongs in thát category) (I want to measure the effects of the different category advertisements on people). The advertisements with the highest ratings (that the raters placed the most often in that category) will be used.

My mentor says I have to use inter-rater reliability. But I feel that Cohen’s Kappa is not usable in this case (because of the 15 raters). But I have no idea how or which test I háve to use.

Hopefully you understand my question and hopefully you can help me out!

Best regards,

Judith

This is not really an ICC question, but I might be able to help. Your mentor is correct; you need to assess the reliability of your ratings. 15 raters is indeed a problem for Cohen’s kappa because it limits you to two raters; you should use Fleiss’ kappa instead – at least for the categorical ratings. You could use ICC for the likability ratings.

Thank you for your quick answer!

However, I use SPSS but the syntax I found online are not working properly (I get only errors). Is there some other way in SPSS (20.0) to calculate Fleiss?

Thank you!

Thank you, Dr. Landers!

Dear Dr Landers,

I’m an orthopaedician trying to assess if three observers measuring the same 20 different bones ( length of the bone) using the same set of calipers and the same method have a large difference when they measure it. I’ve calculated the ICC for intra-observer variation using intraclass 2 way mixed(ssps 16). Do I have to calculate three different ICC’s or can I get all three sets of data together and get a single ICC for all of us? We’ve measured the 20 different bones and the raters were the same. The variables were continuous in mm. And if i cant use ICC what should I use instead to measure inter observer variation between 3 observers?

Another small doubt- during the process of reading about this I chanced upon this article suggesting CIV or coefficient of inter observer variability-

Journal of Data Science 3(2005), 69-83, Observer Variability: A New Approach in Evaluating

Interobserver Agreement , Michael Haber1, Huiman X. Barnhart2, Jingli Song3 and James Gruden

Now do I need to use this as well?

I was referred here by another website that I was reading for information about ICC- 1) i really appreciate that you’ve taken time out to reply to all the questions, and 2)very lucidly explained ( ok, ok, admit I didn’t get the stuff about k and c etc but that’s probably because I m an archetypal orthopod.

regards,

Mathew.

ICC is across raters, so you’ll only have one ICC for each variable measured. So if length of bone is your outcome measure, and it’s measured by 3 people, you’ll have 1 ICC for “length of bone.” ICC also doesn’t assess inter-observer variation – rather the opposite – inter-observer consistency.

There are different standards between fields, so your field may prefer CIV as a measure of inter-rater reliability (I am not familiar with CIV). I can’t really speak to which you should use, as your field is very different from mine! But normally you would not need multiple measures of reliability. I doubt you need both – probably one or the other.

Dear Dr. Landers,

I wanted to know, whether my raters agree with each other and whether anyone of my 10 raters rated so differently, that I have to exclude him. Is the ICC the right measure for that? And is it in my case better to look at the single measures or the average measures?

Regards,

Martina

There isn’t anything built into ICC functions in SPSS to check what ICC would be if you removed a rater; however, it would probably be easiest just to look at a correlation matrix with raters as variables (and potentially conduct an exploratory factor analysis). However, if you believe one of your raters is unlike the others, ensure you have a good argument to remove that person – you theoretically chose these raters because they come from a population of raters meaningful to you, so any variation from that may represent variation within the population which would not be reasonable to remove.

For single vs. average measure, it depends on what you want to do with your ratings. But if you’re using the mean ratings for some other purpose (most common), you want average measures.

Thank you very much for your answer!

Regards,

Martina

Dear Dr. Landers,

Thanks very much. I stuck with ICC.

regards,

Mathew

Dr. Landers,

I have individuals in a team who respond to 3 scale items (associated with a single construct). I would like to aggregate the data to team level (as I have team performance data). How do I calculate the ICC(1) and ICC(2) to justify aggregation? Each of the teams have varying size.

As I mentioned before in an earlier comment, the idea of aggregation in the teams literature is more complex than aggregation as used for coding. For an answer to your question, I’d suggest taking a look at:

Bliese, P. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability. In K. Klein and S. Kozlowski (Eds), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (pp. 349-381).

Hofmann, D. A. (2002). Issues in multilevel research: Theory development, measurement; and analysis. In S. Rogelberg (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Klein, K. l, Dansereau, F., and Hall, Rl (1994). Levels issues in theory development, data collection, and analysis. Academy of Management Review, 19, 195-229.

Dear Dr. Landers,

Your explanation is very helpful to non-statisticians. I have a question. I am doing a test-retest reliability study with only one rater, i.e. the same rater rated the test and retest occasions. Can you suggest which ICC I should use?

Thanks for your advice in advance!

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to calculate inter-rater reliability with only one rater. Even if you want to know the inter-rater reliability of a single rater, you need at least 2 raters to determine that value. If you just want an estimate of reliability, you can use test-retest reliability (a correlation between scores at time 1 and time 2), but it will by definition assume that there is no error in your rater’s judgments (which may or may not be a safe assumption).

Dear Dr. Landers,

I just wanted to express my appreciation for your “labor of love” on this site. Your willingness to provide help (with great patience!) to others struggling with reliability is much appreciated.

From a fellow psychologist…

Jason King

Dear Dr. Landers,

I will be grateful if you can spare some time to answer this.

I am translating an English instrument to measure medication regimen complexity in Arabic. The instrument has three sections and helps to calculate the complexity of medication regimen. I have selected around 10 regimen of various difficulty/complexity for this purpose and plan to use a sample of healthcare professionals such as pharmacists, doctors and nurses to rate them as per the instrument. How do I calculate the minimum number of regimen (though I have selected 10 but can select more) and raters (health care professionals) if I want to test the Inter-rater reliability?

I am not sure I completely understand your measurement situation. It sounds like you want to assess the inter-rater reliability of your translated measure, but I am not sure to what purpose. Are you planning on using this in a validation study? Are you trying to estimate the regimen complexity parameters for your ten regimens? An instrument does not itself have “reliability” – reliability in classical test theory is the product of the instrument by measurement context interaction. So it is not valuable to compute reliability in a vacuum – you only want to know reliability to ultimately determine how much unreliability affects the means, SDs, etc, that you need from that instrument.

Thank you for the comments Dr. Landers,

I want to use the instrument in a validation study to demonstrate the Arabic translation is valid and reliable. For validity, I will be running correlations with the actual number of medications to see if the scale has criterion related validity (increase in number of medications should go hand in hand with increase in complexity scores) and for reliability measurement I was thinking of performing ICC.

Thanks,

Tabish

That is my point – the way you are phrasing your question leads me to believe you don’t understand what reliability is. It is a nonsense statement to say “I want to demonstrate this instrument is reliable” in the context of a single validation study. A particular measure is neither reliable nor unreliable; reliability is only relevant within a particular measurement context, and it is always a matter of degree. If you’re interested in determining how unreliability affects your criterion-related validity estimates in a validation study, you can certainly use ICC to do so. Based upon your description, it sounds like you’d want ICC(1,k) for that purpose. But if you’re asking how many regimen/raters you need, it must be for some specific purpose – for example, if you want a certain amount of precision in your confidence intervals. That is a power question, and you’ll need to calculate statistical power for your specific question to determine that, using a program like G*Power.

Dear Dr Landers

Thank you vefry much for the clear explanation of ICC on your website. There is only one step I do not understand.

We have developed a neighbourhood assessment tool to determine the quality of the neighbourhood environment. We had a pool of 10 raters doing the rating of about 300 neighbourhoods. Each neighbourhood was always rated by two raters. However, there were different combinations (or pairs) of raters for the different neighbourhoods.

This appears a one-way random situation: 600 (2×300) ratings need to be made, which are distributed across the 10 raters (so each rater rated about 60 neighbourhoods).

We now have an SPSS dataset of 300 rows of neighbourhoods by 10 columns of raters. It is however not a *complete* dataset, in the sense that each rater did not rate about 240 (=300-60) neighbourhoods.

I am not sure how we should calculate the ICC here/ or perhaps should input the data differently

Most grateful for your help

ICC can only be used with a consistent number of raters for all cases. Based on your description, it seems like you just need to restructure your data. In SPSS, you should have 2 columns of data, each containing 1 rating (the order doesn’t matter), with 300 rows (1 containing each neighborhood). You’ll then want to calculate ICC(1,2), assuming you want to use the mean of your two raters for each neighborhood in subsequent analyses.