Succeeding at Games Doesn’t Mean Players Enjoy Them

![]() In a recent article in Cyberpsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, Trepte and Reinecke1 explore one potential mediator of the relationship between player performance and game enjoyment: self-efficacy. If players succeeded at the game (played well), they only enjoyed the game if they felt that they were responsible for that success.

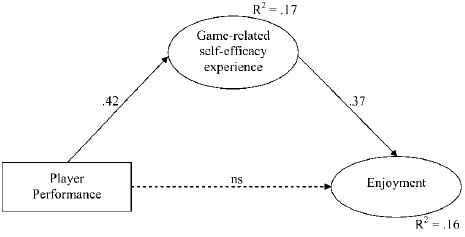

In a recent article in Cyberpsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, Trepte and Reinecke1 explore one potential mediator of the relationship between player performance and game enjoyment: self-efficacy. If players succeeded at the game (played well), they only enjoyed the game if they felt that they were responsible for that success.

To examine this issue, the researchers had 213 research participants play Crazy Chicken: Heart of Tibet, a platformer by Sproing Interactive Media. They played this for 30 minutes, after which they completed several survey measures.

Three variables were used in their analyses:

- Player performance was captured by adding the frequencies of several key game “events,” which included collecting various game items, reaching new levels, activating saves, and so on.

- Self-efficacy, which is the extent to which players believe they are able to succeed at the game, was captured with a previously researched 11-item scale with items like, “I had the impression that I could immediately affect things on the screen.”

- Game enjoyment was captured with a 5-item scale developed for this study (risky!), with items like, “Playing the game was fun.”

Their primary hypothesis was that the relationship between player performance and game enjoyment was mediated by self-efficacy; in other words, in order for player performance to affect enjoyment, it needed to affect self-efficacy first.

So what does that mean, exactly? It means that just because a player succeeds at a game, they’re not necessarily going to enjoy that game. For example, if the game is very easy such that they never feel challenged, even if they are playing extremely well, they are less likely to enjoy the game. If they have self-efficacy experiences (e.g. being challenged and overcoming those challenges), they are more likely to enjoy the game. This is reminiscent of another study I reported on recently on the cognitive state of confusion leading to engagement in learning games.

Unfortunately, there are weaknesses to this study. It relies on structural equation modeling (SEM; a complex statistical procedure allowing for the estimation of multiple relationships simultaneously, which is generally a good thing) but doesn’t really use it convincingly. SEM, you see, is easy to manipulate. Reporting a single set of model fit statistics doesn’t really tell you much about whether your theory makes sense because finding fit is not all that difficult. To identify a model with good fit, one wants high CFIs and low RMSEAs, but high CFI and low RMSEA is almost the standard state of affairs. If your model even sort of makes sense, you’ll find “acceptable” fit statistics.

Instead, the real power of SEM is model comparison. When you have two alternate ways of looking at the same data and want to see which fits better, you are unleashing the real power of SEM. What would have been more helpful here would have been to examined other competing hypotheses. For example, perhaps the relationship between self-efficacy and enjoyment are mediated by player performance, i.e. instead of what the researchers reported, perhaps experiences of self-efficacy lead to enjoyment, but only if that high self-efficacy leads to higher performance. There is prior research supporting both of these models, but the researchers only tested one of these; that’s a shame, since they have the data to have tested both. Determining which approach fit better would be much more informative.

Self-efficacy is also operationalized a little oddly here. Generally when we think of self-efficacy, we think of self-efficacy for success – answers to the question, “If I were to play this game, would I succeed?” Here, the researchers are asking, “If I were to play this game, would my actions lead to improved game performance?” This is actually closer to the definition of expectancy, part of Vroom’s VIE theory of motivation.

Regardless, this study does provide evidence that consideration of internal motivational processes is important in the development of games (and by extension, learning games). Modeling these complexities explicitly will be useful for better explaining player behavior.

- Trepte, S., & Reinecke, L. (2011). The pleasures of success: Game-related efficacy experiences as a mediator between player performance and game enjoyment. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0358 [↩]

| Previous Post: | Recruit Top Talent with Web Sites That Combat Industry Stereotypes |

| Next Post: | How People Have Bad Experiences on Online Social Networks |

Trackbacks and Pingbacks