The Privacy Paradox: Why People Who Complain About Privacy Also Overshare

![]() In an upcoming issue of the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Taddicken1 explores a phenomenon called the privacy paradox, a term that describes how social media users report that they are concerned about their privacy but do very little to actively protect it. In this study, 2739 German Internet users were surveyed to help identify why people overshare despite such concerns. In her study, roughly 30% of social media users reported sharing personal photos without any access restrictions, and roughly 17% reported sharing their thoughts, experiences, thoughts, feelings, concerns and fears to the wide open Internet.

In an upcoming issue of the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Taddicken1 explores a phenomenon called the privacy paradox, a term that describes how social media users report that they are concerned about their privacy but do very little to actively protect it. In this study, 2739 German Internet users were surveyed to help identify why people overshare despite such concerns. In her study, roughly 30% of social media users reported sharing personal photos without any access restrictions, and roughly 17% reported sharing their thoughts, experiences, thoughts, feelings, concerns and fears to the wide open Internet.

Two personality traits were found to drive sharing: a person’s desire to talk about themselves regardless of situation, followed by the degree to which people found social media to be relevant to their personal social lives. So as it turns out, many people do want it both ways: they want to enrich their social lives by talking about themselves online to anyone who will listen, but they don’t want this information to be read by just anyone. Apparently their desire to be social is simply stronger than their desire to protect their privacy. The important implication here is that it implies simply teaching people about privacy and how to safeguard their information isn’t going to work; the desire to share with others is too strong.

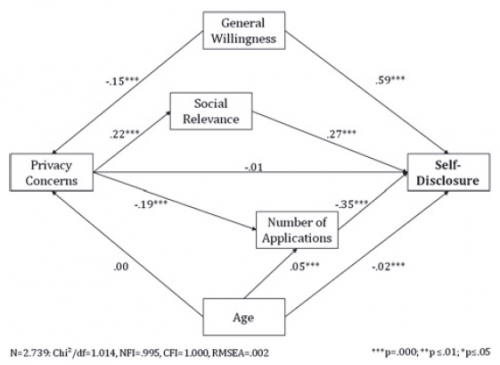

Privacy concerns did affect sharing, but only indirectly. Greater privacy concerns were weakly associated with lower willingness to self-disclose, and willingness to self-disclose was strongly positively associated with actual sharing. Greater privacy concerns were also weakly associated with smaller number of joined social media platforms, and the number of social media platforms joined was moderately associated with less self-disclosure. So this brings what appears to me to be a new paradox: people more concerned about privacy join fewer sites, but those that join fewer sites tend to share more on those sites.

The research also identified a difference between two types of personal information: factual (last name, birth date, professional, and postal address) and “sensitive” (photos, experiences, thoughts, feelings, concerns and fears). Roughly 90% of respondents provided first names and email addresses on social media, so given the lack of variation, these were not included in further analyses. Other factual information was shared at least once on social media by 54.6% of respondents, although only 10% did so without restricting who could see it.

Sensitive information was a little more complicated. In general, fewer individuals share sensitive information than basic factual information (first names and email addresses), but more individuals share sensitive information than private factual information. So the specific nature of sharing was a little complicated:

- Roughly 80% of respondents had shared their last name, birth date and profession at least once on social media. Of those sharing at least once, about 63% restricted access to it.

- Roughly 50% of respondents had shared their postal address, and among those sharing at least once, about 90% restricted access to it.

- Roughly 60% of respondents had shared photos, experiences, and thoughts at least once. Of those sharing such things, about 60% restricted access to it.

- Roughly 40% of respondents had shared their feelings, concerns and fears at least once. Of those sharing such things, about 70% restricted access to it.

Overall, this study provides an interesting look into some personality drivers of self-disclosure on the Internet. It is not, however, an exhaustive model. The model presented here would fit just as well in several other configurations, which would alter the path coefficients obtained – for example, joining lots of websites might make users less concerned about privacy, which might in turn drive self-disclosure. Further research will need to explore these components experimentally to get to the heart of causation in this matter.

- Taddicken, M. (2014). The ‘privacy paradox’ in the social web: The impact of privacy concerns, individual characteristics, and the perceived social relevance on different forms of self-disclosure Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19, 248-273 : 10.1111/jcc4.12052 [↩]

| Previous Post: | Gamification, Social Media, Mobile, and MTurk SIOP 2014 TNTLab Research |

| Next Post: | Using Links And Writing About Morality Increase Perceived Credibility |