How Do We Design Effective Video Games for Learning? (VG Series Part 4/10)

Neo-Academic coverage of the Journal of General Psychology special issue on the psychology of video games:

- Is Video Game Research Influenced by the Media?

- Does Personality Predict Vulnerability to Violence in Games?

- Can Spatial Cognition Be Trained with Video Games?

- How Do We Design Effective Video Games for Learning?

- Can Video Games Be Used in Health Care?

- Should Children with Autism Play Video Games?

- Should Video Games Be Used in Therapy?

- Can Video Games Get People to Vote?

- How Do Video Games Motivate People?

- How Do Typical Gamers Play Games?

![]() There are few topics so hotly debated on the Internet as the value of video games. Are they the next generation’s artistic advance, as film was for the last, or are they a blight that makes children overly aggressive and dangerous? In this 10-part series, I’m reviewing a recent special issue of the Journal of General Psychology on video games. For more background information, see the first post in the series.

There are few topics so hotly debated on the Internet as the value of video games. Are they the next generation’s artistic advance, as film was for the last, or are they a blight that makes children overly aggressive and dangerous? In this 10-part series, I’m reviewing a recent special issue of the Journal of General Psychology on video games. For more background information, see the first post in the series.

Finally, something closer to my own research area. The fourth article in the series is Leonard Annetta’s “The “I’s” Have It: A Framework for Serious Educational Game Design.”1

There are several interesting points here. The first I came across was mention of a video game authoring program for teaching being developed at North Carolina State University. I’ll let Annetta tell you about it:

students and scholars are working to create a video game authoring platform where teachers and students can create their own games that align with content standards in science, mathematics, and technology education, although the platform is usable in many other domains. This is not a new idea but rather a recycling of many proven educational theories and practices into the video game world.

I hunted around for some material on NCSU’s website and could not find much more information than that, although I assume it is related to their Digital Games Research Center. That’s too bad; this sounds quite promising (and is similar to a research area my wife is working on!).

Annetta begins by introducing several terms that I myself have struggled at times to distinguish: serious games, serious educational games, simulations, and virtual worlds. To Annetta, serious games include all games that are designed to train someone in a particular skill set. To me, this is a very limited definition – what about games designed to change attitudes or provide perspective? He continues by defining serious educational games as serious games in a K-20 context – an unnecessary distinction, I think. A simulation is defined as a serious game without either 1) score-keeping or 2) the use of virtual or real currency to trade in-game items. I suppose a serious game examining stock market trading would not be a simulation, while Minecraft would be a simulation. Finally, virtual worlds are large, open-ended environments designed for social interaction (although I generally think of these as MUVEs). In this article, Annetta focuses on serious educational games alone, although I see no reason that the other categories would not apply as well.

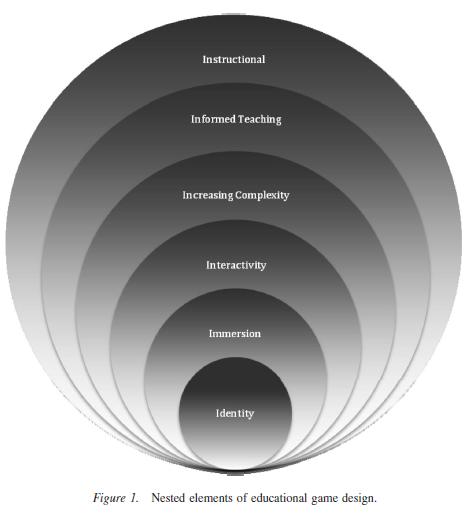

Within this context, a 6-I model is introduced as a way to consider game design, with each progressive I a larger category containing the previous I:

- Identity. This is the narrowest category, focused on establishing individualism in virtual environments. A study is cited in which students could not pick very different avatars from their classmates, and thus never were able to establish a unique virtual identity for themselves, which in turn led to negative engagement and immersion outcomes for the students. Which brings us to…

- Immersion. Most of the value from serious gaming, according to Annetta, comes from their “ability to capture the player’s mind and trick him/her into believing he or she is a unique individual in the environment.” Doing this (i.e., establishing identity) creates a sense of immersion, or presence, in the virtual environment. A poor sense of immersion means that a student is never fully engaged (although no empirical evidence of this seems to be presented).

- Interactivity. A very interesting study is briefly discussed under this heading – apparently, people experience the same sorts of social inhibitions in the presence of nonplayer characters (NPCs; game characters controlled by the computer) as they do in the presence of player characters (PCs; game characters controlled by real people). I’m not sure if the players were aware when the other characters were PCs or NPCs, but it is certainly a provocative finding. It is, unfortunately, the only empirical finding really discussed that directly applies to this “I”.

- Increased Complexity. I’m not sure what to think of this quote: “There is a balancing act when designing complex SEGs. This is not unlike designing a complex science activity. It involves juggling multiple objectives, choosing what to prioritize and when, what to defer, and what conceptual levels to tap.” That’s true of all instruction, isn’t it? What is unique about serious educational gaming?

- Informed Teaching. This section discusses the difficulties in collecting accurate research data on what students are doing when playing educational games. I’m not quite sure what that has to do with “informed teaching,” but it presents a feature as a disadvantage that I consider an advantage: there can be a vast amount of collected data from studies of educational gaming. One of the advantages to all interaction taking place on a computer is that you can collect a record of literally everything the player does. I suppose this is a disadvantage if the only kind of data analysis you’re familiar with is ANOVA, but the types of data modeling that could be used here make this a very promising area indeed.

- Instructional. This I pushes that all of the previous Is are necessary to make quality educational games, which I’m not sure merits its own category. More interestingly, the concept of adaptable video games is discussed, and I agree that there is real possibility here: “Content that comes easily for the most gifted students causes those students to get bored as they wait for the teacher to work with their peers who did not assimilate the content as easily. Conversely, students who grapple with difficult concepts or content are often left behind if the teacher decides to challenge the students who understood the material with ease. An SEG with artificial intelligence could challenge the students who ‘get it’ and scaffold learning for those who do not.” This, I think, is the most promising area of both video games and web-based training (i.e. my) research – educational systems than can adapt themselves to the needs of the learner could dramatically alter the instructional landscape. Imagine a classroom where every student learned as their own pace – quick but not too quick – and everyone received the individualized attention they needed to excel. A bright future indeed.

So overall, is this model a good framework for educational game design? Sort of. The principles listed here are certainly interesting, and it may provide a starting point for research in this domain. These are certainly provocative issues to consider. But the use of a multi-layered circles-within-circles model? Probably not justified.

Perhaps more critically, no attention is paid to the value of this framework over previous or alternative frameworks for general instructional design. Is it really all that different to design educational games than it is to design in-person games? Does only the technology differ, or is there really something fundamentally different about these computer-based environments? I am not convinced that this current view offers anything incrementally valuable over generally accepted models of instruction, and this article provides little to try to convince otherwise.

- Annetta, L. (2010). The “I’s” have it: A framework for serious educational game design. Review of General Psychology, 14 (2), 105-112 DOI: 10.1037/a0018985 [↩]

| Previous Post: | Can Spatial Cognition Be Trained with Video Games? (VG Series Part 3/10) |

| Next Post: | Can Video Games Be Used in Health Care? (VG Series Part 5/10) |

Thanks for sharing my work. I have moved from NC State, which is why you might not have been able to find much. I’d be glad to share more.